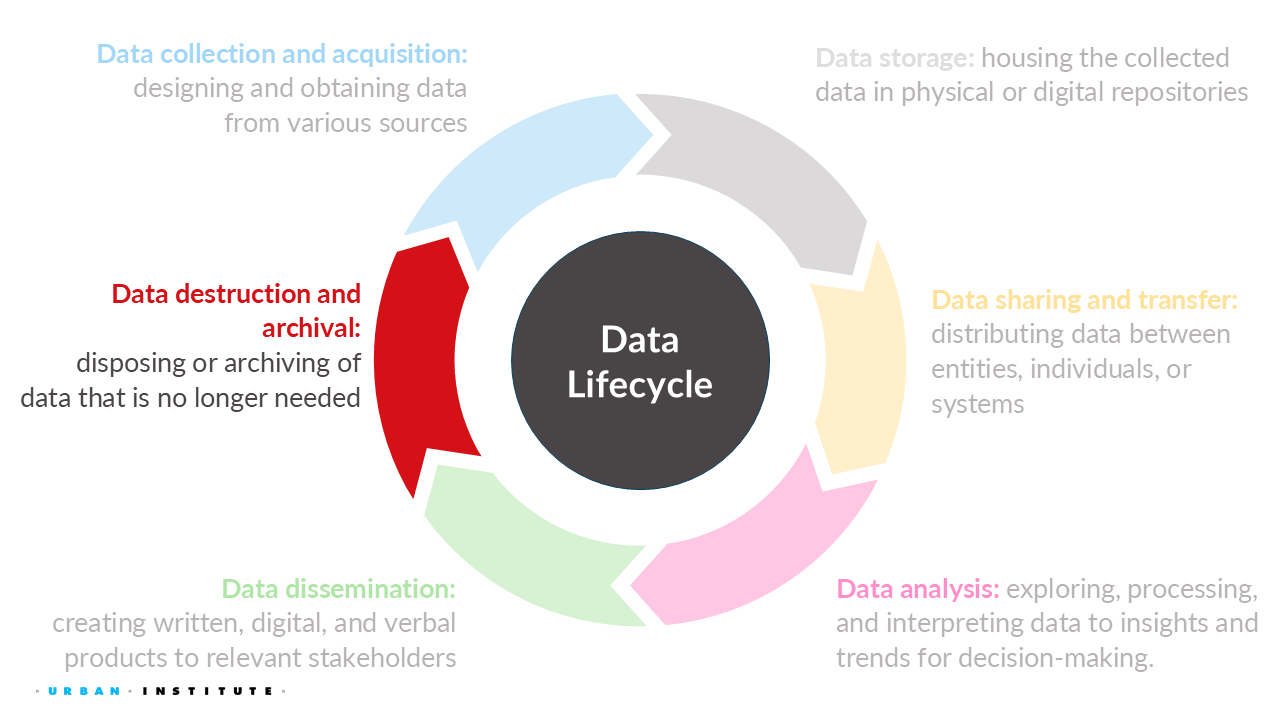

10 Data Destruction or Termination + Future Challenges

For this week, we will learn the importance of destroying or terminating data along with future challenges.

10.1 Quick recap on week 5

10.1.1 Data privacy laws in the United States of America

The laws governing data collection and dissemination are limited to specific federal agencies (e.g., U.S. Census Bureau) or specific data types (e.g., education).

The California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) gives consumers more control over the personal information that businesses collect about them, with accompanying regulations that provide guidance on how to implement the law. In November 2020, California voters approved Proposition 24, the California Privacy Rights Act, which amended the CCPA and added additional privacy protections that took effect on January 1, 2023.

10.1.2 Identifying the technical and policy solutions

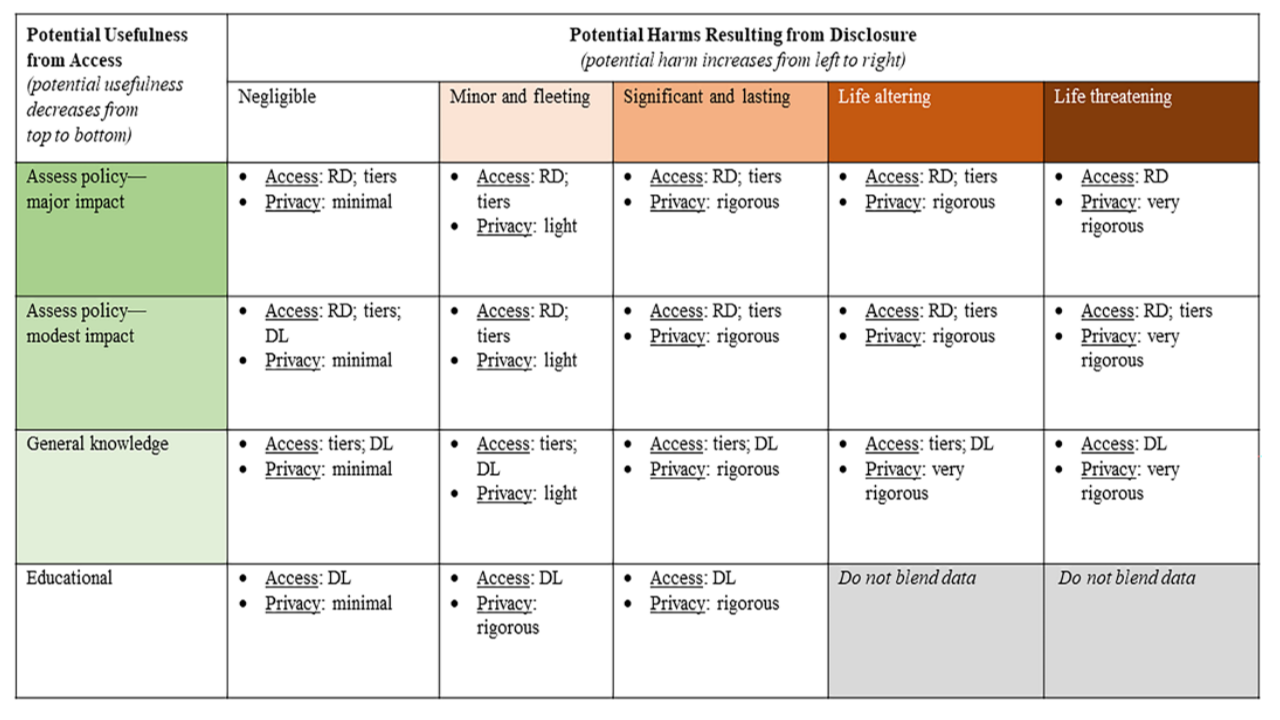

Decision matrix

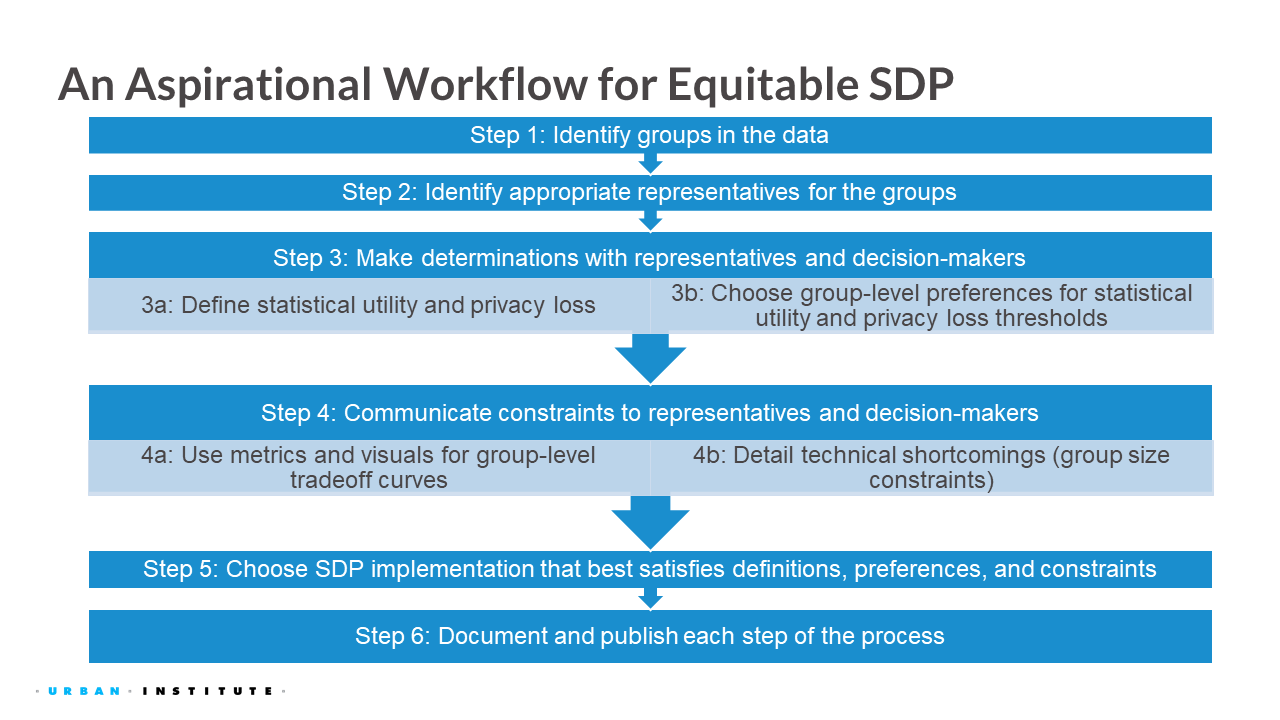

Aspirational equitable statistical data privacy workflow

A Framework for Managing Disclosure Risks in Blended Data

Determine auspice and purpose of the blended data project.

- What are the anticipated final products of data blending?

- What are potential downstream uses of blended data?

- What are potential considerations for disclosure risks and harms, and data usefulness?

Determine ingredient data files.

- What data sources are available to accomplish blending, and what are the interests of data holders?

- What steps can be taken to reduce disclosure risks and enhance usefulness when compiling ingredient files?

Obtain access to ingredient data files.

- What are the disclosure risks associated with procuring ingredient data?

- What are the disclosure risk/usefulness trade-offs in the plan for accessing ingredient files?

Blend ingredient data files.

- When blending requires linking records from ingredient files, what linkage strategies can be used?

- Are resultant blended data sufficiently useful to meet the blending objective?

Select approaches that meet the end objective of data blending.

- What are the best-available scientific methods for disclosure limitation to accomplish the blended data objective, and are sufficient resources available to implement those methods?

- How can stakeholders be engaged in the decision-making process?

- What is the mitigation plan for confidentiality breaches?

Develop and execute a maintenance plan.

- How will agencies track data provenance and update files when beneficial?

- What is the decision-making process for continuing access to or sunsetting the blended data product, and how do participating agencies contribute to those decisions?

- How will agencies communicate decisions about disclosure management policies with stakeholders?

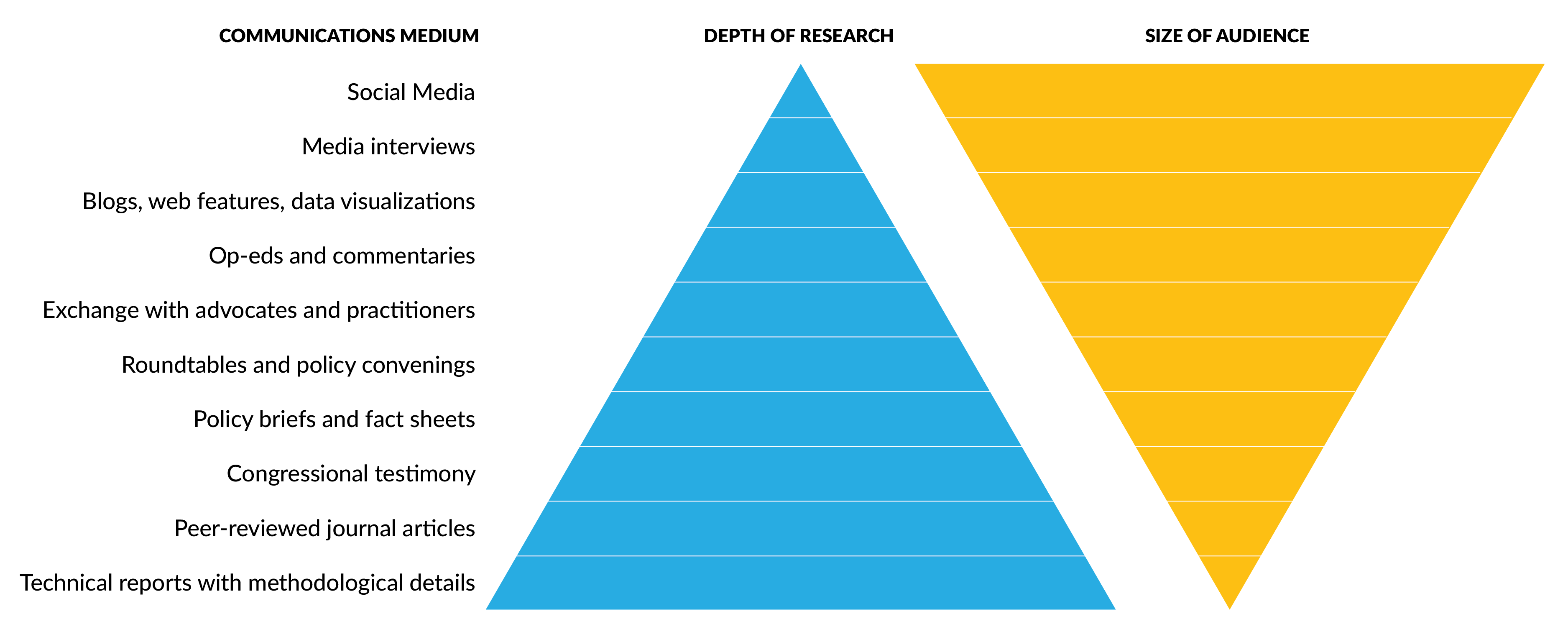

10.1.3 Types of dissemination

10.1.4 Data visualizations

Similar to outlining a presentation, don’t race to the computer. Start with paper and pen (or color pencils/markers!), chalkboard and chalk, etc. to sketch out your data visualization.

- Show the data

- Reduce the clutter

- Integrate the graphics and text

- Avoid Speghetti chart

- Start with gray

10.1.5 Week 6 Assignment

Read

- Chapter 7: What Is the Future of Data Privacy?

Optional additional read

Write (600 to 1200 words)

Throughout this course, we’ve explored the intersections of data privacy, security, and ethics. Drawing on the topic you picked for your presentation (or can be an example from course readings and discussions so far), respond to the following prompts:

- What data did the AI system, algorithm, or example you selected use to shape what was shown to you (e.g., content, recommendations, decisions)?

- Does this scenario apply broadly to the general population, or primarily to a specific subgroup? Explain your reasoning.

- Could the example you discussed be repurposed or modified to serve a public good? If so, what changes would be necessary?

- Would those changes raise new considerations around security, privacy, or ethics? If yes, describe them.

OR

An academic reached out to me to share that he’s been experimenting with an AI-generated podcast based on technical articles from the Journal of Economic Perspectives, the assigned article reading, so he can learn about economics while walking. Based on your readings and listening to the AI generated podcast:

How did your understanding of the article differ between reading it and listening to the AI‑generated podcast? Did one format make the ideas clearer or raise new questions for you?

What do you see as the potential benefits and drawbacks of using AI‑generated podcasts (or similar tools) to engage with complex topics like privacy and administrative data?

If more academic content were delivered through AI‑generated audio, what ethical or quality concerns should educators and researchers keep in mind?

10.2 Data destruction or termination (or archival)

Upon project or dissemination completion, it is important to consider the appropriate handling of all copies of confidential data. This may involve physical destruction or, where permitted, archival, in accordance with legal requirements (e.g., data use agreements) or agreements with data subjects (e.g., informed consent).

In cases where data archiving is warranted, all direct identifiers should be removed. A name-code index, if necessary, must be stored separately in a secure location to maintain confidentiality.

For data analysis projects involving confidential information—such as Personally Identifiable Information (PII), Personal Health Information (PHI), or financial data, there is often a requirement to destroy the data within a specified period after the project concludes. These requirements are typically outlined in data use agreements, contracts, or institutional policies.

Data destruction must follow approved methods, especially for data stored in readily accessible formats (e.g., hard drives, cloud storage). Some agreements may require formal documentation of the destruction process. In such cases, organizations may issue a Certificate of Destruction or a similar verification document.

Additionally, certain contracts may stipulate that the destruction process be witnessed or notarized, requiring a third party to confirm that the data has been securely and irreversibly destroyed.

Most private companies and other entities have their own policies for data disposal. Generally, acceptable methods fall into two categories: logical and physical.

10.2.1 Logical

Logical destruction involves erasing data with multiple read/write commands, such as those performed by Pretty Good Privacy1 File Shredder or by emptying the file system’s recycle bin.

10.2.2 Physical

Physical disposal involves destroying the data media itself, such as shredding paper documents and CDs/DVDs, degaussing magnetic media, or drilling holes through hard drives.

10.2.3 Data destruction types

The National Institute of Standards and Technology 800-88 standard Guidelines for Media Sanitization defines three primary methods for data destruction:

Clear– Uses logical techniques to sanitize data in all user-addressable storage locations, protecting against simple, non-invasive data recovery methods. This is typically done using standard read/write commands, such as overwriting data with new values or using a factory reset option (when overwriting is not supported).

Purge – Applies physical or logical techniques that make data recovery infeasible, even with advanced laboratory methods.

Destroy – Physically renders media unusable and ensures that data recovery is infeasible using state-of-the-art techniques.

The Department of Defense 5520.22 M standard specifies a minimum of three overwrite passes to securely erase electronic data:

- Pass 1: Overwrite with all zeroes

- Pass 2: Overwrite with all ones

- Pass 3: Overwrite with random data

This multi-pass method ensures that data cannot be recovered, even with physical access to the storage medium.

10.2.4 Ethics and equity considerations

In addition to security and privacy considerations, we should think about the ethical and equity reasons for destroying data. Some points to consider are:

- How should researchers who collect data inform participants about data destruction policies without impacting the data collection process?

- Consider the transparency aspect.

- Are there situations where destroying data could be unethical?

- Consider scenarios where data could be valuable for future research versus scenarios where its existence might cause harm.

- How might data destruction disproportionately impact marginalized or vulnerable populations?

- Consider how to engage stakeholders.

10.3 Future Challenges

Data curators, stakeholders, privacy experts, and data users all face ongoing challenges in expanding the use of government data—particularly when linking administrative and survey data. Unless data privacy can be robustly protected, access to such data is likely to remain limited or restricted entirely.

10.3.1 Educating the data ecosystem

Little is known about the expectations and needs of various entities within the data ecosystem who do not specialize in privacy, security, and ethics. As an example, Williams et al. (2023) conducted a convenience sample survey of economists from the American Economic Association on their baseline knowledge about differential/formal privacy (the concept used on the 2020 Census), attitudes toward differentially/formally private frameworks, types of statistical methods that are most useful to economists, and how the injection of noise under formal privacy would affect the value of the queries to the user. At a high level, the survey found that most economists are unfamiliar with formal privacy and differential privacy (and if they know about it, they are skeptical). Instead, economists rely on simple methods for analyzing cross-sectional administrative data but have a growing need to conduct more sophisticated research designs, and economists have low tolerance for errors, which is incompatible with existing formal privacy definitions and methods.

The results from the Williams et al. (2023) survey are not surprising. In general, traditional PETs are more intuitive and easier to explain, such as why data curators should remove unique records. In contrast, formally private methods are more complex and lack an intuitive definition. Although there has been an explosion of new communication materials to explain formal privacy and other data privacy concepts,2 such efforts are trying to fill a chasm and we are not even close.

One way to address the shortage of educational and communication materials on security, privacy, and ethics throughout the data lifecycle is to teach the next generation and grow the field. However, most higher education institutions lack dedicated courses on the topic. When the topic is taught, it’s typically at the graduate level within computer science departments. Some undergraduate professors may introduce these concepts in seminars, but standalone courses are rare. As a result, individuals from other technical disciplines, such as economics,are often underrepresented.

To bridge this gap, departments beyond computer science should consider offering their own courses on PETs or integrating these topics into existing curricula. In doing so, instructors can encourage students to explore the legal, social, and ethical dimensions of data privacy, including principles of data guardianship, custodianship, and permissions (Williams and Bowen 2023).

10.3.2 Tiered Access

In a blog post, former U.S. Under Secretary for Economic Affairs, Jed Kolko, identified three types of research most useful to public policymakers:

- Development of new economic measures

- Broad literature reviews

- Quantitative or simulated policy analyses

The third category often relies on access to high-quality data—either through public-use files or secure/restricted environments. The value of the latter is underscored by (Nagaraj and Tranchero 2024), who found that research using confidential microdata from the Federal Statistical Research Data Centers (FSRDCs) is more likely to be cited in policy documents and results in 24% more publications in top-tier journals annually.

As we learned earlier in the course, people interested in obtaining direct access to confidential data face several barriers:

- Eligibility restrictions (e.g., U.S. citizenship)

- Limited geographic access to FSRDCs

- Lengthy approval processes for certain datasets

These challenges can prevent researchers, analysts, and policymakers from using data that could inform critical decisions.

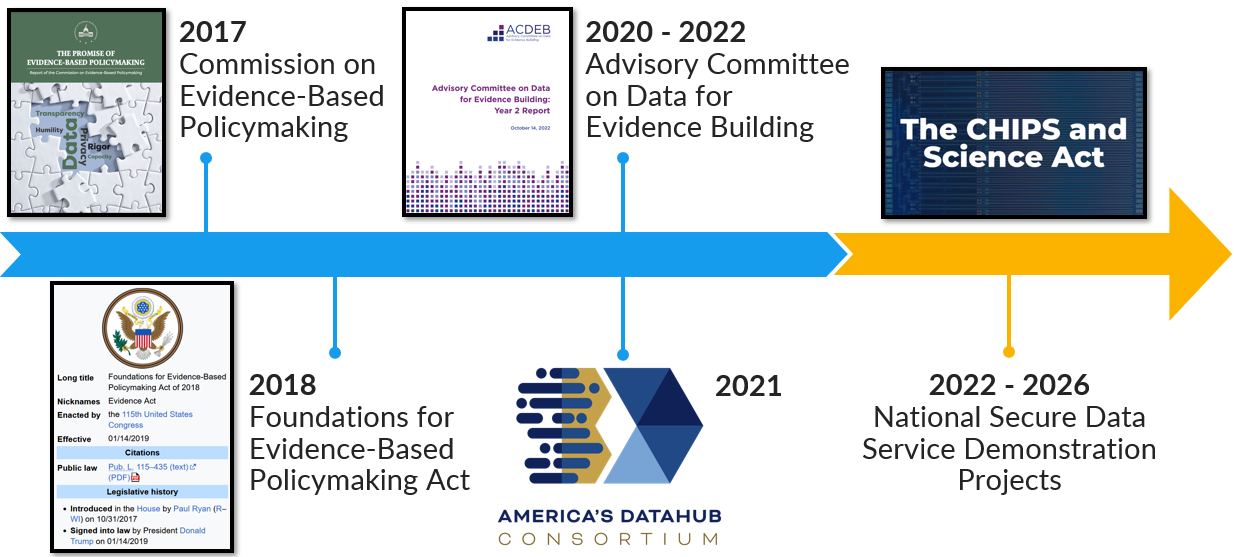

To address this, experts have proposed tiered access models — offering options between fully public-use files and highly restricted secure data. Created under the Foundations for Evidence-Based Policymaking Act of 2018, the National Secure Data Service (NSDS) is designed to improve access to administrative data across all levels of government. Its goals include:

- Providing secure, privacy-preserving data access

- Supporting data linkage across agencies

- Offering shared services like a data concierge and secure tools

To test this vision, the National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics has launched NSDS Demonstration Projects, which explore practical solutions to technical and policy challenges in building a future NSDS.

10.4 Final Presentation

Due August 11, 4 pm EDT (at the time of class)

10.4.1 Prepare to present!

5-minute presentation/pitch. Details discussed in week 4 (July 14) class.

“Pretty Good Privacy is an encryption program that provides cryptographic privacy and authentication for data communication.” from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pretty_Good_Privacy↩︎

One of my favorites is a video created by minutephysics for the US Census Bureau, available at “Protecting Privacy with MATH (Collab with the Census),” (accessed on June 27, 2024).↩︎