We start with data collection and learn about the different types of data, the importance of how we collect that data, and the issues for society caused by the absence of or poorly designed data collection.

But first…

Quick recap on week 1

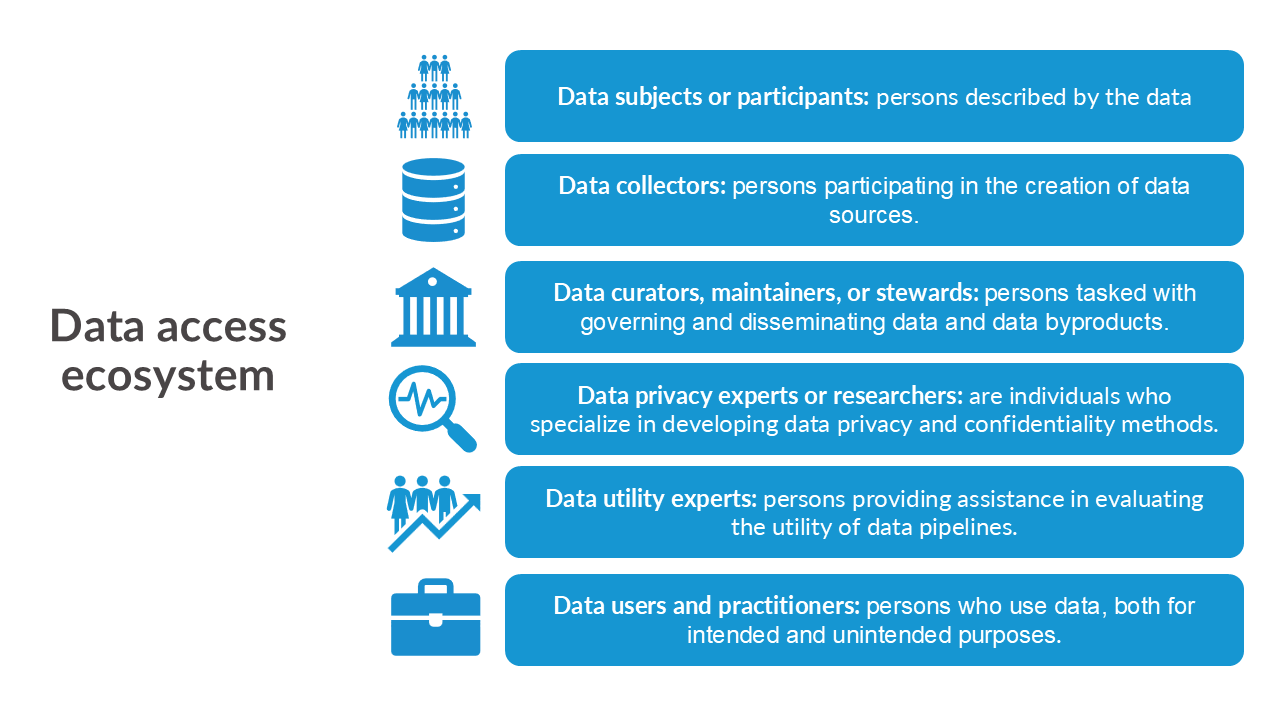

We should consider the interactions within this ecosystem and the data life cycle in the context of security, privacy, ethics, and equity.

Definitions

Data Security is the “…science of methods of protecting computer data and communication systems that apply various types of controls such as cryptography, access control, information flow paths and inference control, including backup and recover” (Denning 1982).

Data Privacy is the ability “to determine what information about ourselves we will share with others” (Fellegi 1972). Data privacy is a broad topic, which includes data security, encryption, access to data, etc. We will not be covering privacy breaches from unauthorized access to a database (e.g., hackers).

Confidentiality is “the agreement, explicit or implicit, between data subject and data collector regarding the extent to which access by others to personal information is allowed” (Fienberg and Jin 2018).

- Hackers: adversaries who steal confidential information through unauthorized access.

- Snoopers: adversaries who reconstruct confidential information from data releases.

- Hoarders: stewards who collect data but don’t release the data even if respondents want the information releasesd.

Data ethics is the “…systemizing, defending, and recommending concepts of right and wrong conduct in relation to data, in particular personal data” (Kitchin 2014).

Data Equity is data representation, access, process, outcomes, and more.

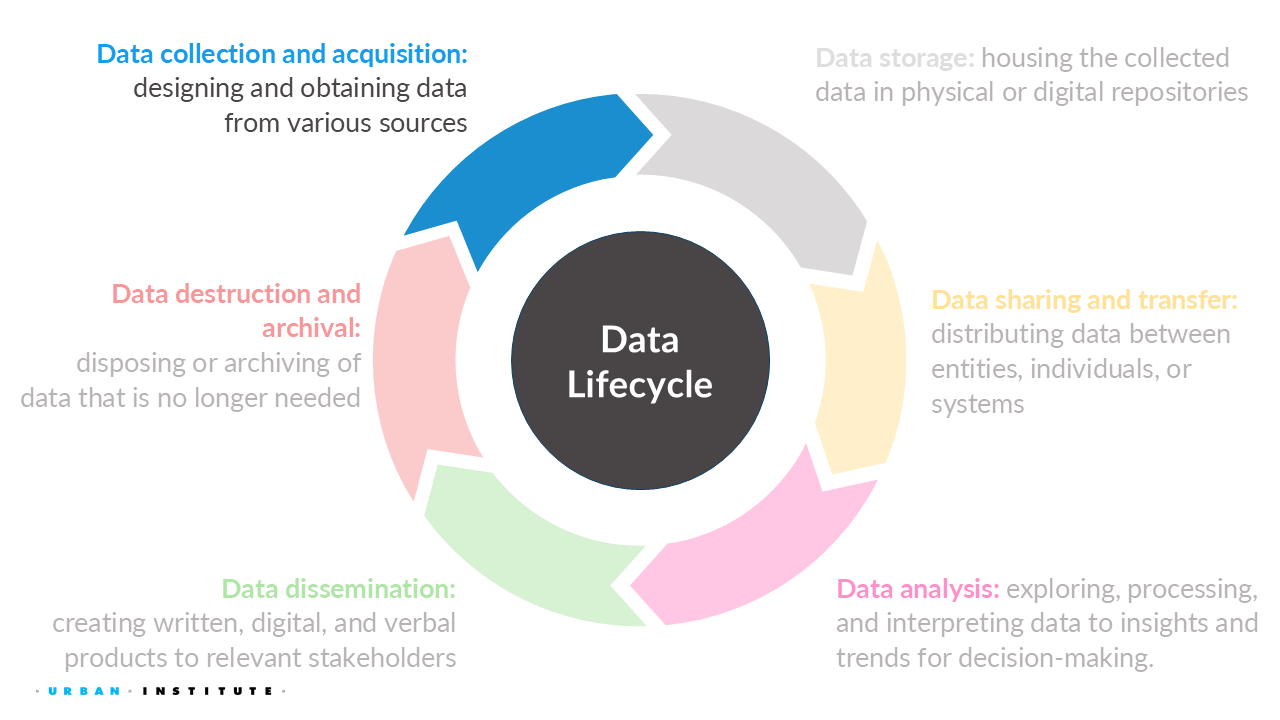

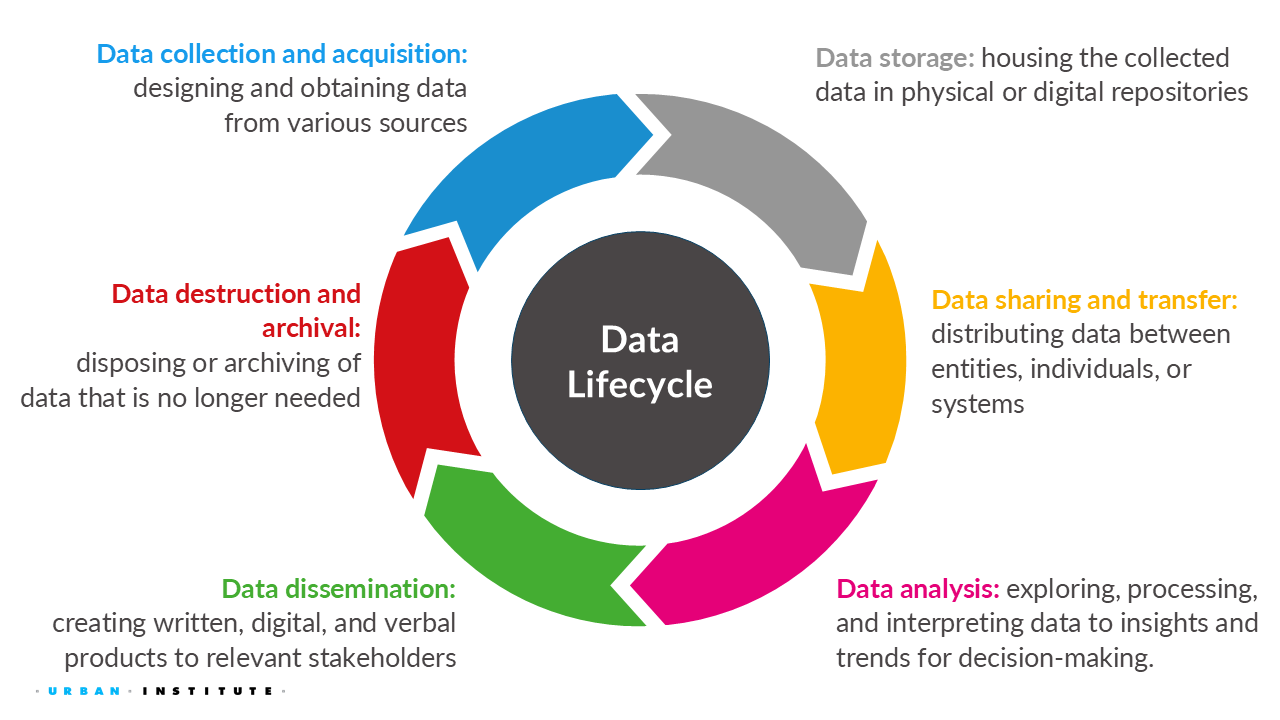

We’ve just started exploring the world of security, privacy, ethics, and equity. Throughout this course, we’ll integrate these definitions, concepts, and ideas into our discussions, applying them to the data life cycle, which we define as:

data collection or acquisition (week 2)

data storage (week 3)

data sharing and transfer (week 3)

data analysis (week 4)

data dissemination (week 5)

data destruction or termination (week 6)

Week 2 Assignment

Write (600 to 1200 words)

Find and summarize a real-world example of data being used unethically and/or had violated people’s privacy. The example must be recent (i.e., since 2022). Try to keep the following in mind:

- What is the example? Introduce the situation and explain why it is important, providing any relevant background for the reader.

- How did the example demonstrate a violation of privacy, security, and/or ethics? Does it apply to everyone or only a subgroup of people? Why is that?

- What are the takeaways from this situation? Has this situation been resolved? Why or why not?

What was your example of unethical or harmful data use, and who was most affected?

How might applying principles from the readings thus far (e.g., Do No Harm or privacy-enhancing methods) have changed the outcome?

What lessons should data practitioners or analysts take away from this case to prevent similar issues in the future?

Data types

There are generally three principal types of qualitative and quantitative data:

Primary: Any data directly collected by an entity.

Secondary: Any data collected by another organization that a stakeholder uses for analysis.

Administrative: Any data collected by governments or other organizations, as part of their management and operation of a program or service, that provide information on registrations, transactions, and other regular tasks.

Primary data

Direct data collection includes both quantitative data (e.g., from a survey) and qualitative data (e.g., from focus groups, site visits, qualitative interviews, or trained observations) collected from individuals or organizations. Also, with primary you will usually have access to paradata.

Secondary data

Secondary data also include both quantitative and qualitative data; depending on the source, they may also include some paradata. Often, secondary data are in public-use files that have been sanitized for general release and use (e.g., public file of the American Community Survey).

Administrative data

Administrative data are collected for the administration of an organization or program by entities, such as government agencies as they provide services, companies to track orders, and universities to record registered students. These data records are usually not public-use data files and tend to only be accessed through strict confidentiality agreements, such as non-disclosure agreements or memorandum of understanding (e.g., IRS tax payer data).

For each data type:

- What are some other examples?

- What are the possible security, privacy, ethical, and equity considerations and challenges?

- If these challenges are not addressed, what are the potential downstream impact?

Discussion on Do No Harm Guide: Collecting, Analyzing, and Reporting Gender and Sexual Orientation Data

If equity isn’t considered in the design of the study for that small subgroup, then it’s not the main purpose of the study. Other parts will take priority. Afterall, what was the study designed for?

~ Saki Kinney, RTI (Research Triangle International)

This quote from a colleague highlights the importance of how data are collected. If we blindly collect data without careful consideration of the process—such as how we define groups or the methods used for data collection—we could severely and negatively impact those groups when others in the data ecosystem use and analyze that data.

The required reading assignment, Do No Harm Guide (DNHG) by Schwabish et al. (2023), covers many data collection challenges and will facilitate our discussion on the potential security, privacy, ethical, and equity issues in data collection.

Defining groups is important

Collecting data about sexual orientation and gender identity and expression allows for a better understanding of sexual and gender minority populations, enabling researchers, policymakers, and advocates to understand differences between these populations and other population groups or the general population across policy areas. Insight from these data highlight important areas for interventions that may improve the lives of members of sexual and gender minority groups.

There is a glossary at the start of the DNHG instead of at the end.

- Why do you think the authors had the glossary so early in the report?

- Do you think the government, schools, or other organizations that collect data use the same definition when collecting data?

- What is the impact of not having a standard definition for each stakeholder in the data ecosystem?

How do we define ourselves and society

There are two sides to survey data collection: the experience of the participant and the experience of the researcher. Thus, building trust between the participant and the researcher is key to generating high-quality data. Communicating to people why their personal information is necessary and gaining their formal consent can lead to greater collaboration and, ultimately, allow for more inclusive survey methods.

Part 3 of the DNHG reviews various methods for conducting surveys to collect sexual orientation and gender identity information. This highlights the challenge of properly defining groups in a way that is both consistent and inclusive.

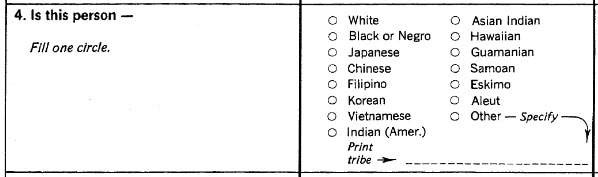

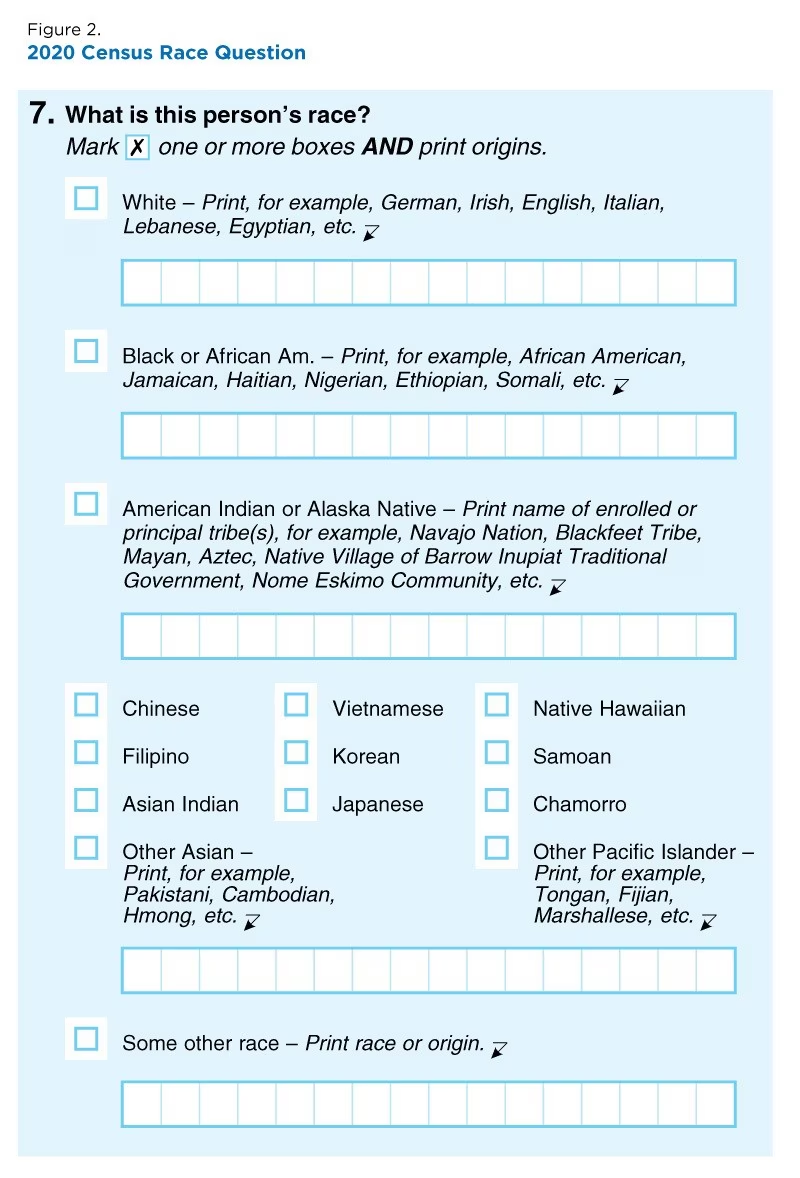

Article I, Section 2 of the Constitution mandates that a census must take place every 10 years in the United States. The data collected by the decennial census determine the number of seats each state has in the U.S. House of Representatives and how to distribute the trillions in federal funds to local communities.

As part of the decennial census, people must answer several questions, such as what is their race. How would define your race?

The images below show the race question for the 1990 and 2020 Census questionnaire. Would your definition match what is offered in these questionnaires?

The nuances of different races is important in some contexts and not in others. For example, the state of Wyoming probably only needs to know the number of Asian Americans (i.e., coarsen all subgroups into the larger group), whereas New York City needs the count of various subgroups, because each subgroup has different poverty rates (Sonoda and Hahn 2023).

No data, no problem, no action

We will cover two real-world example sets where the lack of data or improper data collection negatively impacts downstream data analysis.

Library of Missing Datasets

Do you agree or disagree that we should answer the following questions with data?

- Sales and prices in the art world (and relationships between artists and gallerists)

- People excluded from public housing because of criminal records

- Trans people killed or injured in instances of hate crime (note: existing records are notably unreliable or incomplete)

- Poverty and employment statistics that include people who are behind bars

- Muslim mosques/communities surveilled by the FBI/CIA

- Mobility for older adults with physical disabilities or cognitive impairments

- LGBT older adults discriminated against in housing

- Undocumented immigrants currently incarcerated and/or underpaid

- Undocumented immigrants for whom prosecutorial discretion has been used to justify release or general punishment

- Measurements for global web users that take into account shared devices and VPNs

- Firm statistics on how often police arrest women for making false rape reports

- Master database that details if/which Americans are registered to vote in multiple states

- Total number of local and state police departments using stingray phone trackers (IMSI-catchers)

- How much Spotify pays each of its artists per play of song

What if you were then told that there are no such datasets created or available to answer these questions?

These questions are part of a mixed-media installation by Mimi Ọnụọha called, The Library of Missing Datasets, which is on version 3.0. This piece is a physical repository of those things that have been excluded in a society where so much is collected.

From Mimi Onuoha’s website,

“Missing datasets” are the blank spots that exist in spaces that are otherwise data-saturated. Wherever large amounts of data are collected, there are often empty spaces where no data live. The word “missing” is inherently normative. It implies both a lack and an ought: something does not exist, but it should. That which should be somewhere is not in its expected place; an established system is disrupted by distinct absence. That which we ignore reveals more than what we give our attention to. It’s in these things that we find cultural and colloquial hints of what is deemed important. Spots that we’ve left blank reveal our hidden social biases and indifferences.

Mimi Ọnụọha created the list of questions for “The Library of Missing Datasets 3.0” in 2022. Her GitHub repo indicates that one of the illustrative examples from her version 2 installation in 2018 is no longer missing.

Civilians killed in encounters with police or law enforcement agencies [update: this is no longer a missing dataset]

In the next 10 to 15 minutes, pick one of the example questions from the “Library of Missing Datasets 3.0” and try to find a publicly available dataset that answers that question.

Did you find a dataset that works? If not, did you find a dataset that was close? Why did the dataset not answer the question?

Mimi Ọnụọha says there are many reasons why some potentially important datasets are missing and highlights four reasons:

- Those who have the resources to collect data lack the incentive to (corollary: often those who have access to a dataset are the same ones who have the ability to remove, hide, or obscure it).

Police brutality towards civilians provides a powerful example. Though policing and crime are among the most data-driven areas of public policy, traditionally there has been little history of standardized and rigorous data collected about police brutality. Nowadays we have a political and cultural climate where this issue has become one of public discussion. Public interest campaigns like Fatal Encounters and the Guardian’s The Counted have helped fill that void. But even for these individuals/organizations, the work is difficult and time-consuming. The group who would make the most sense to monitor this issue—the law enforcement agents who create the data set in the first place—have no incentive to actually gather such data, which could prove incriminating.

- The data to be collected resist simple quantification (corollary: we prioritize collecting things that fit our modes of collection).

The defining tension of data collection is the struggle of taking a messy, organic world and defining it in formats that are neat, clean, and structured. Some things are difficult to collect and quantify by nature of their structure. We don’t know how much US currency is outside of our borders. There’s no incentive for other countries to monitor US currency within their countries, and the very nature of cash and the anonymity it affords makes it difficult to track. But then there are other subjects that resist quantification entirely. Things like emotions are hard to quantify (at this time, at least). Institutional racism is subtle and deniable; it reveals itself more in effects than acts. Not all things are easily quantifiable, and at times the very desire to render the world more abstract, trackable, and machine-readable is an idea that itself deserves questioning.

- The act of collection involves more work than the benefit the presence of the data is perceived to give.

Sexual assault and harassment are woefully underreported. And while there are many reasons why this is, one major one is that in many cases the very act of reporting sexual assault is a very intensive, painful, and difficult process. For some, the benefit of reporting isn’t perceived to be equal or greater than the cost of the process.

- There are advantages to nonexistence.

Every missing dataset is a testament to this fact. Just as the presence of data benefits someone, so too does the absence. This is important to keep in mind. However, there’s an even more specific angle to this point. To collect, record, and archive aspects of the world is an intentional act, one that typically benefits those who have the power to decide what should be collected. Often, remaining outside of the bounds of collection can be a form of response for a situationally-disadvantaged group. In short, sometimes a missing dataset can function as a form of protection.

If you could not find a dataset, why do you think that dataset doesn’t exist based on the four reasons Mimi Ọnụọha highlighted?

Asian Americans are highly educated, born in the U.S., and speak English

Not collecting data is one issue. Another, which could be just as or even more detrimental to society, is collecting the wrong kind of data. If we are not careful with how we design data collection, we could create harmful narratives about certain areas of society, especially underrepresented groups.

An example of this is work done by my colleague, Dr. Sunghee Lee of the University of Michigan. She presented her in the same conference session as me, where she discussed how incomplete data on Asian-American populations risks fueling a vicious circle of inaction and growing inequality. One of her projects compared the socio-demographics of Asian-American respondents reported in four large-scale sample surveys against the same characteristics collected by the US Census Bureau’s American Community Survey, which is often referred to as the gold standard survey on the United States populations and housing information (Tarran 2023).

When comparing these surveys, Dr. Lee found that the four surveys often differed in important respects. For example, Asian Americans accounted for seven percent of adults aged 18 and over in the American Community Survey. In contrast, the General Social Survey and Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Survey accounted for only four percent and two percent, respectively. The American Community Survey shows 27 percent of Asian-American respondents are educated to high-school level or below, the equivalent grouping in the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Survey accounted for 18 percent.

However, none of these surveys, except the American Community Survey, collected data on Asian Americans’ proficiency with spoken English.

According to the American Community Survey, 31 percent of Asian-American adults have “limited English proficiency.” Dr. Lee’s research found that none of the four selected surveys (General Social Survey and Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Survey, plus the Current Population Survey and National Health Interview Survey) offered questionnaires in Asian languages; only English and Spanish.

Due to the poorly designed surveys, anyone using these data will find that most Asian Americans are born in the US and/or who have high levels of English proficiency, missing the true geographic and ethnic heterogeneity of the Asian American population. This underrepresentation of certain Asian-American subgroups encourages a potential vicious cycle of having no “data-driven” proof to collect such information. This means that issues affecting certain population groups are not identified, meaning no action needs to be taken.

Hence, at the end of the presentation, Dr. Lee’s slide stated, “No data, no problem, no action”.

After learning about this use case, answer the following:

- What is your reaction to this situation?

- Can you think of other situations where a lack of data would lead to no action because no one knows there is a problem?

Week 3 Assignment

Due July 13th, Sunday, at 11:59 pm EDT on Canvas

Read

- Chapter 4: How Do Data Privacy Methods Avoid Invalidating Results?

Write (600 to 1200 words)

Choose a community you belong to (e.g., your hometown, childhood community, or Stonehill College) and identify how it uses public federal datasets (e.g., from the U.S. Census Bureau, Department of Transportation, etc.) to inform a policy decision.

Describe the specific use case you’ve identified and analyze how limiting or expanding access to that data (or multiple data sources) could impact your community.

Example (that you can’t use): School district lines.

Denning, Dorothy Elizabeth Robling. 1982. Cryptography and Data Security. Vol. 112. Addison-Wesley Reading.

Fellegi, Ivan P. 1972. “On the Question of Statistical Confidentiality.” Journal of the American Statistical Association 67 (337): 7–18.

Fienberg, Stephen E, and Jiashun Jin. 2018. “Statistical Disclosure Limitation for~ Data~ Access.” In Encyclopedia of Database Systems (2nd Ed.).

Kitchin, Rob. 2014. The Data Revolution: Big Data, Open Data, Data Infrastructures and Their Consequences. Sage.

Schwabish, Jonathan, Donovan Harvey, Mel Langness, Vincent Pancini, Amy Rogin, and Gabi Velasco. 2023. “Do No Harm Guide: Collecting, Analyzing, and Reporting Gender and Sexual Orientation Data.”

Sonoda, Paige, and Heather Hahn. 2023.

“Disaggregating Data Is Critical to Dismantling the Model Minority Stereotype.” https://www.urban.org/urban-wire/disaggregating-data-critical-dismantling-model-minority-stereotype.