8 Data Dissemination: Part 1

For this week, we will learn the different aspects of disseminating data while considering security, privacy, ethics, and equity. In part 1, we focus on the legal and policy side before disseminating your work.

8.1 Quick recap on week 4

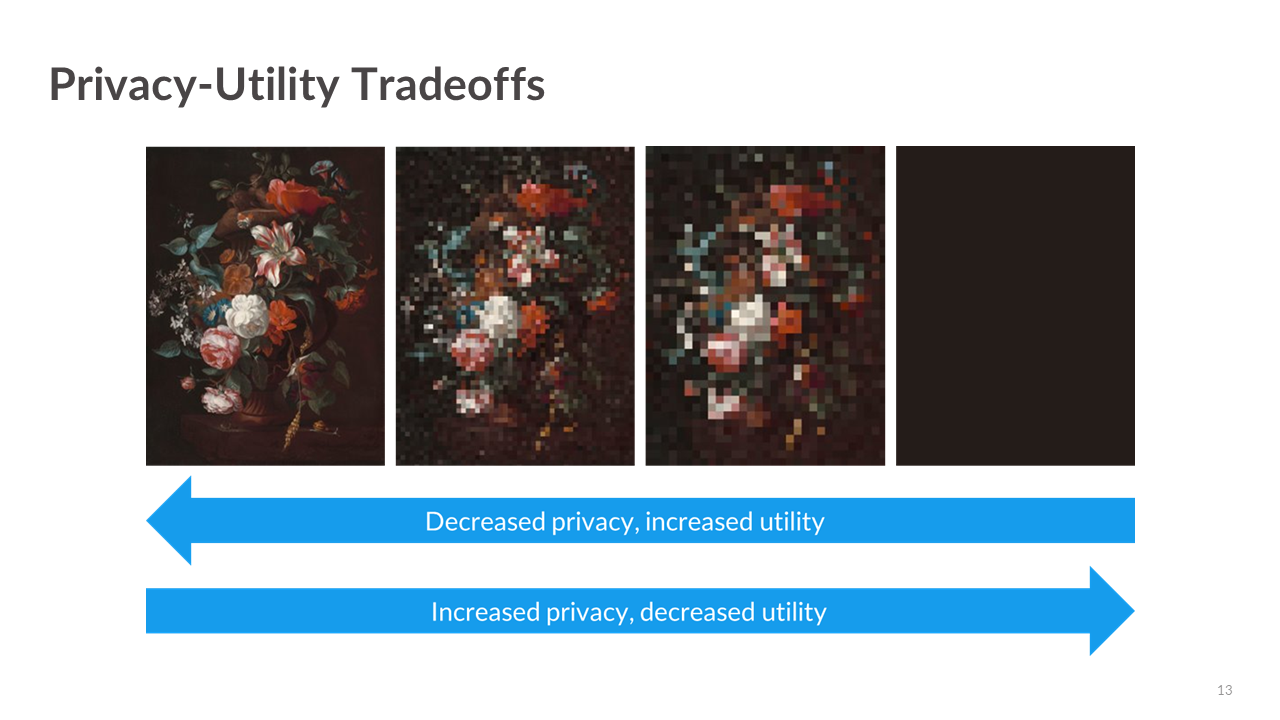

8.1.1 Privacy-utility tradeoff

There is often a tension between privacy and data utility. This tension is referred to in the privacy literature as the privacy-utility tradeoff.

Data utility, quality, accuracy, or usefulness is how practically useful or accurate to the data are for research and analysis purposes.

8.1.2 Assessing utility

Generally there are three ways to measure utility of the data:

General utility, sometimes called global utility, measures the univariate and multivariate distributional similarity between the confidential data and the public data (e.g., sample means, sample variances, and the variance-covariance matrix).

Specific utility, sometimes called outcome specific utility, measures the similarity of results for a specific analysis (or analyses) of the confidential and public data (e.g., comparing the coefficients in regression models).

Fit-for-purpose, are something in between the previous two utility metric types to quickly assess the quality of the public data compared to the confidential data. They are not global measures, because they focus on certain features of the data, but may not be specific to an analysis that data users and stakeholders are interested in like analysis-specific utility metrics.

8.1.3 Assessing disclosure risk

Note that most thresholds for acceptable disclosure risk are often determined by law.

There are generally three kinds of disclosure risk:

Identity disclosure occurs if the data intruder associates a known individual with a public data record (e.g., a record linkage attack or when a data adversary combines one or more external data sources to identify individuals in the public data).

Attribute disclosure occurs if the data intruder determines new characteristics (or attributes) of an individual based on the information available through public data or statistics (e.g., if a dataset shows that all people age 50 or older in a city are on Medicaid, then the data adversary knows that any person in that city above age 50 is on Medicaid). This information is learned without idenfying a specific individual in the data!

Inferential disclosure occurs if the data intruder predicts the value of some characteristic from an individual more accurately with the public data or statistic than would otherwise have been possible (e.g., if a public homeownership dataset reports a high correlation between the purchase price of a home and family income, a data adversary could infer another person’s income based on purchase price listed on Redfin or Zillow).

8.1.5 Week 5 Assignment

Read

- Chapter 6: What Data Privacy Laws Exist?

Optional additional read

Optional watch

Collect data

For one day, record how often private companies collect your data from the moment you wake up to the moment you go to bed. For example, opening a social media app or browsing the web.

Write (600 to 1200 words)

Based on your data log, answer the following questions:

- Is any of the information collected by private companies protected by a state or federal law?

- What could a private company do with that information for the public good?

- What could a private company do with that information that may harm or violate your personal privacy?

- What are the data equity and ethical impacts of collecting this information?

8.2 Data privacy laws in the United States of America

Prior to releasing any information (e.g., data and statistics), you must review the legal requirements. As you learned from the book and the questionnaire in the first week of class, the United States has no federal law regulating how personal data can be collected, stored, and used. A privacy policy does not equate to data privacy protections.

The laws governing data collection and dissemination are limited to specific federal agencies (e.g., U.S. Census Bureau) or specific data types (e.g., education).

8.2.1 Federal privacy laws

CIPSEA establishes uniform confidentiality protections for information collected for statistical purposes by U.S. statistical agencies, and it allows some data sharing between the Bureau of Labor Statistics, Bureau of Economic Analysis, and Census Bureau. The agencies report to Office of Management and Budget on particular actions related to confidentiality and data sharing.

The law gives the agencies standardized approaches to protecting information from respondents so that it will not be exposed in ways that lead to inappropriate or surprising identification of the respondent. By default the respondent’s data is used for statistical purposes only. If the respondent gives informed consent, the data can be put to some other use.

From Wiki.

A reauthorization of CIPSEA in 2018-19 gave the statistical agencies more opportunities to use administrative data for statistical purposes, and required them to more deeply analyze risks to privacy and confidentiality of respondents.

Foundations for Evidence-Based Policymaking Act of 2018 is often referred to as the Evidence Act and updated CIPSEA.

This Act protects children’s privacy by giving parents tools to control what information is collected from their children online. The Act requires the Commission to promulgate regulations requiring operators of commercial websites and online services directed to children under 13 or knowingly collecting personal information from children under 13 to: (a) notify parents of their information practices; (b) obtain verifiable parental consent for the collection, use, or disclosure of children’s personal information; (c) let parents prevent further maintenance or use or future collection of their child’s personal information; (d) provide parents access to their child’s personal information; (e) not require a child to provide more personal information than is reasonably necessary to participate in an activity; and (f) maintain reasonable procedures to protect the confidentiality, security, and integrity of the personal information. In order to encourage active industry self-regulation, the Act also includes a “safe harbor” provision allowing industry groups and others to request Commission approval of self-regulatory guidelines to govern participating websites’ compliance with the Rule.

From the Federal Trade Commission.

The FERPA is a federal law that affords parents the right to have access to their children’s education records, the right to seek to have the records amended, and the right to have some control over the disclosure of personally identifiable information from the education records. When a student turns 18 years old, or enters a postsecondary institution at any age, the rights under FERPA transfer from the parents to the student (“eligible student”). The FERPA statute is found at 20 U.S.C. § 1232g and the FERPA regulations are found at 34 CFR Part 99.

From the U.S. Department of Education

The HIPAA Privacy Rule establishes national standards to protect individuals’ medical records and other individually identifiable health information (collectively defined as “protected health information”) and applies to health plans, health care clearinghouses, and those health care providers that conduct certain health care transactions electronically. The Rule requires appropriate safeguards to protect the privacy of protected health information and sets limits and conditions on the uses and disclosures that may be made of such information without an individual’s authorization. The Rule also gives individuals rights over their protected health information, including rights to examine and obtain a copy of their health records, to direct a covered entity to transmit to a third party an electronic copy of their protected health information in an electronic health record, and to request corrections.

From the The HIPAA Privacy Rule from U.S. Department of Human and Health Services.

Effective as of June 25, 2024: HIPAA Privacy Rule To Support Reproductive Health Care Privacy will “…strengthen privacy protections for medical records and health information for women.”

The Census Bureau is bound by Title 13 of the United States Code. These laws not only provide authority for the work we do, but also provide strong protection for the information we collect from individuals and businesses.

Title 13 provides the following protections to individuals and businesses:

- Private information is never published. It is against the law to disclose or publish any private information that identifies an individual or business such, including names, addresses (including GPS coordinates), Social Security Numbers, and telephone numbers.

- The Census Bureau collects information to produce statistics. Personal information cannot be used against respondents by any government agency or court.

- Census Bureau employees are sworn to protect confidentiality. People sworn to uphold Title 13 are legally required to maintain the confidentiality of your data. Every person with access to your data is sworn for life to protect your information and understands that the penalties for violating this law are applicable for a lifetime.

- Violating the law is a serious federal crime. Anyone who violates this law will face severe penalties, including a federal prison sentence of up to five years, a fine of up to $250,000, or both.

From the U.S. Census Bureau

The Internal Revenue Code (IRC) is the body of law that codifies all federal tax laws, including income, estate, gift, excise, alcohol, tobacco, and employment taxes. U.S. tax laws began to be codified in 1874, but there was no central, comprehensive source for them at that time. The IRC was originally compiled in 1939 and overhauled in 1954 and 1986. This code is the definitive source of all tax laws in the United States and has the force of law in and of itself.

These laws constitute Title 26 of the U.S. Code (26 U.S.C.A. § 1 et seq. [1986]) and are implemented by the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) through its Treasury Regulations and Revenue Rulings.

Congress made major statutory changes to Title 26 in 1939, 1954, and 1986. Because of the extensive revisions made in the Tax Reform Act of 1986, Title 26 is now known as the Internal Revenue Code of 1986 (Pub. L. No. 99-514, § 2, 100 Stat. 2095 [Oct. 22, 1986]).

From the U.S. Census Bureau

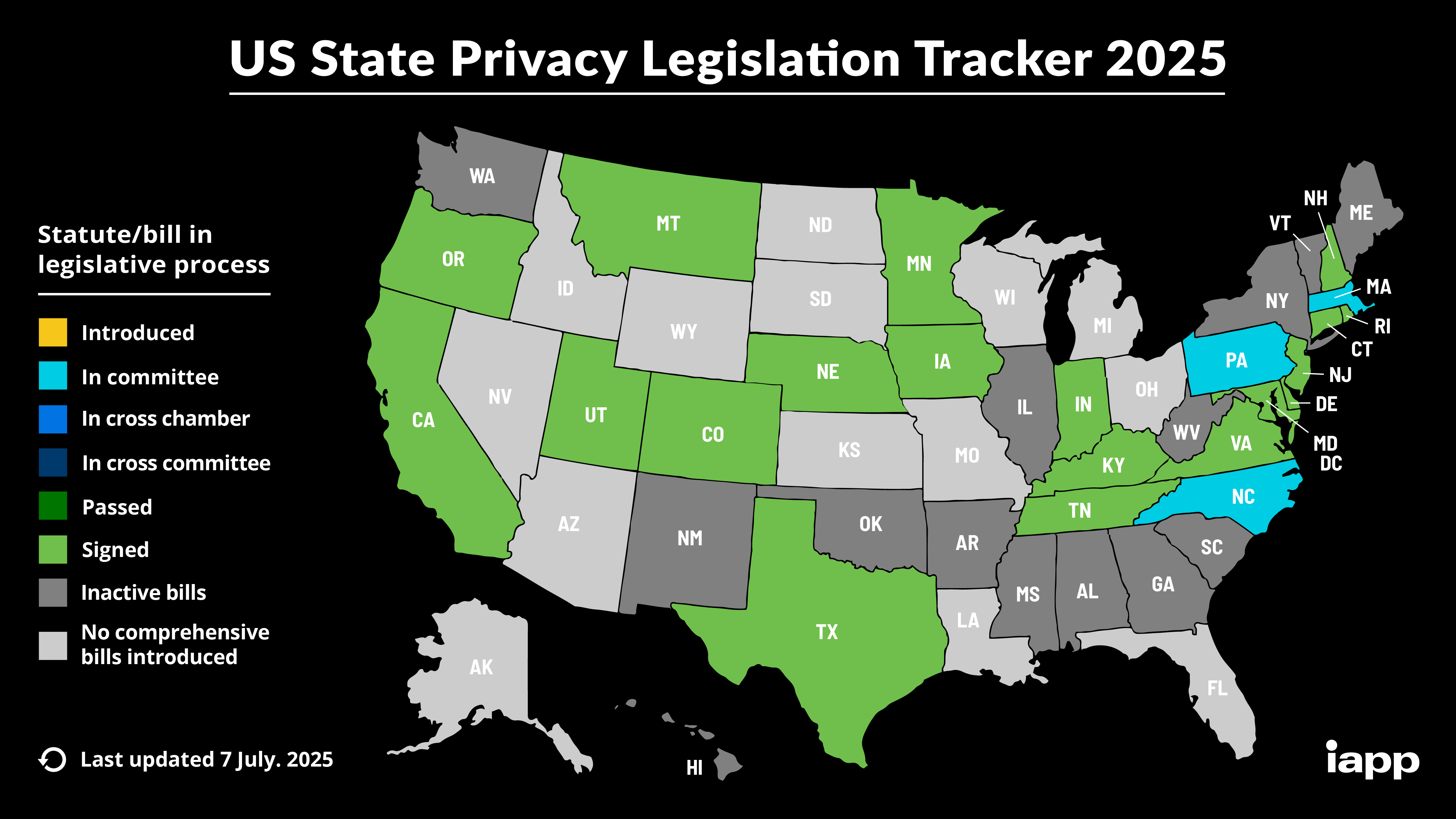

8.2.2 State privacy laws

The International Association of Privacy Professionals (IAPP)1 has a great U.S. State Privacy Legislation Tracker.

State-level momentum for comprehensive privacy bills is at an all-time high. The IAPP Westin Research Center actively tracks the proposed and enacted comprehensive privacy bills from across the U.S. to help our members stay informed of the changing state privacy landscape. This information is compiled into a chart, map and a directory with information specific to states with enacted laws. The IAPP additionally hosts a US State Privacy topic page, which regularly updates with the latest state privacy news and resources, and a US State AI Governance Legislation Tracker, which tracks US state cross-sectoral laws with direct application to the use of AI systems in the private sector.

8.2.3 California Privacy Act of 2018

From the State of California Department of Justice:

The California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) gives consumers more control over the personal information that businesses collect about them, with accompanying regulations that provide guidance on how to implement the law, which includes:

- The right to know about the personal information a business collects about them and how it is used and shared;

- The right to delete personal information collected from them (with some exceptions);

- The right to opt-out of the sale or sharing of their personal information; and

- The right to non-discrimination for exercising their CCPA rights.

In November 2020, California voters approved Proposition 24, the California Privacy Rights Act, which amended the CCPA and added additional privacy protections that took effect on January 1, 2023. As of this date, consumers have new rights in addition to those above, such as:

- The right to correct inaccurate personal information that a business has about them; and

- The right to limit the use and disclosure of sensitive personal information collected about them.

Businesses subject to the CCPA have several responsibilities, including responding to consumer requests to exercise these rights and providing consumers with certain notices explaining their privacy practices. The CCPA applies to many businesses, including data brokers.

8.3 Identifying the technical and policy solutions

Technical and policy approaches in combination are necessary for effective management of disclosure risks.

Agencies and private companies can use a variety of technical and policy approaches, possibly in combination, to achieve disclosure risk/usefulness trade-offs that are acceptable to various stakeholders. Confronted with myriad options, how can an entity arrive at an ideal approach?

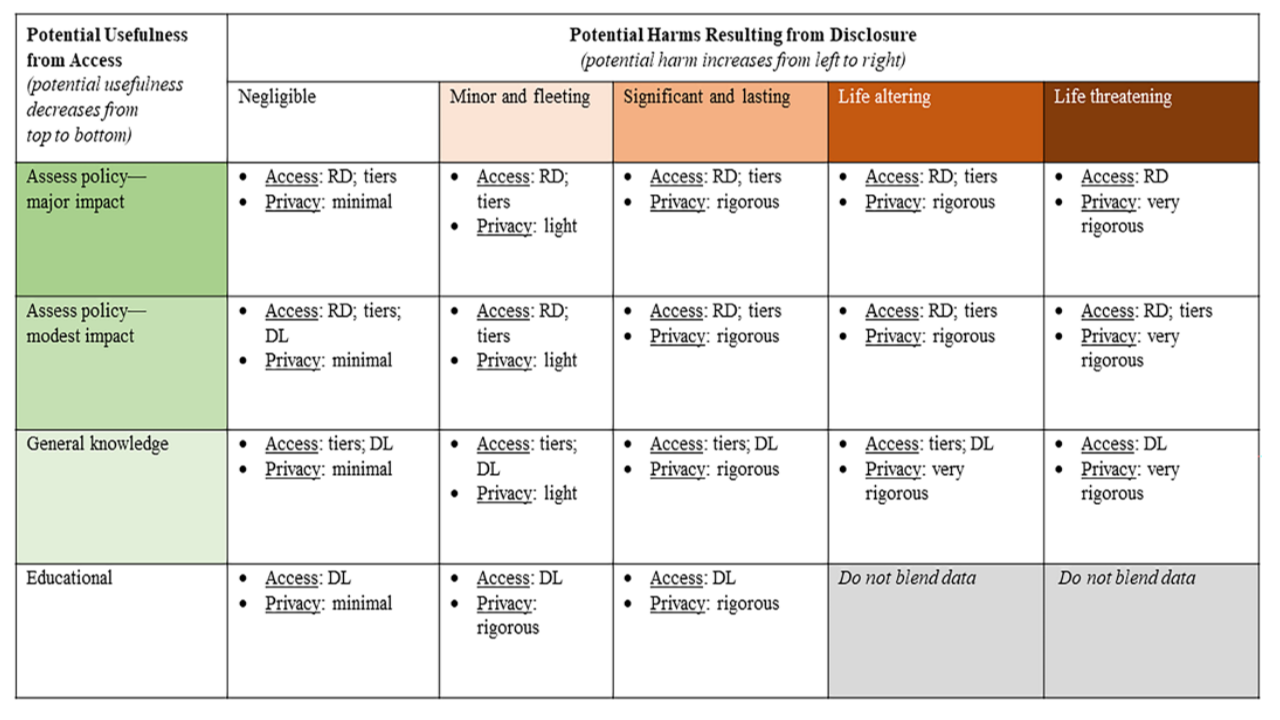

Answers to this question are necessarily context specific. However, some decision points are common to many data dissemination scenarios.

In the interior cells, “Access” refers to approaches that could be particularly effective for managing disclosure risk/usefulness trade-offs. “RD” refers to restricted data, which includes policy approaches like secure data enclaves, licensing and other data-use agreements, penalties and incentives for responsible use, and query auditing. “DL” refers to disclosure limitation, which includes techniques like formal privacy, secure multiparty computation, and synthetic data approaches. “Tiers” refers to tiered access, which may include validation/verification of results from redacted data and access to confidential data under policy restrictions. “Privacy” refers to a general characterization of the desired privacy protections/guarantees on blended data products.

8.3.1 Current statistical data privacy workflow

The current standard workflow for statistical data privacy applications includes three main components: (1) data, (2) privacy practitioner(s), and (3) decisionmaker(s). At the start, privacy practitioners review the data (at the least the data schema2) and talk with the decisionmakers. From there, the privacy practitioners determine the privacy loss and utility framework of definitions, with possible input from the data and the decisionmakers. Decisionmakers then choose the threshold levels of privacy loss and utility, which depend on the legal or societal context and any practical constraints.

From here, the privacy practitioner selects the PETs that meets the desired privacy loss and utility definitions and thresholds. This decision may also use information from the data. Finally, after all the prior decisions are made, the privacy practitioner implements the PETs on the data. In some instances, feedback loops exist.

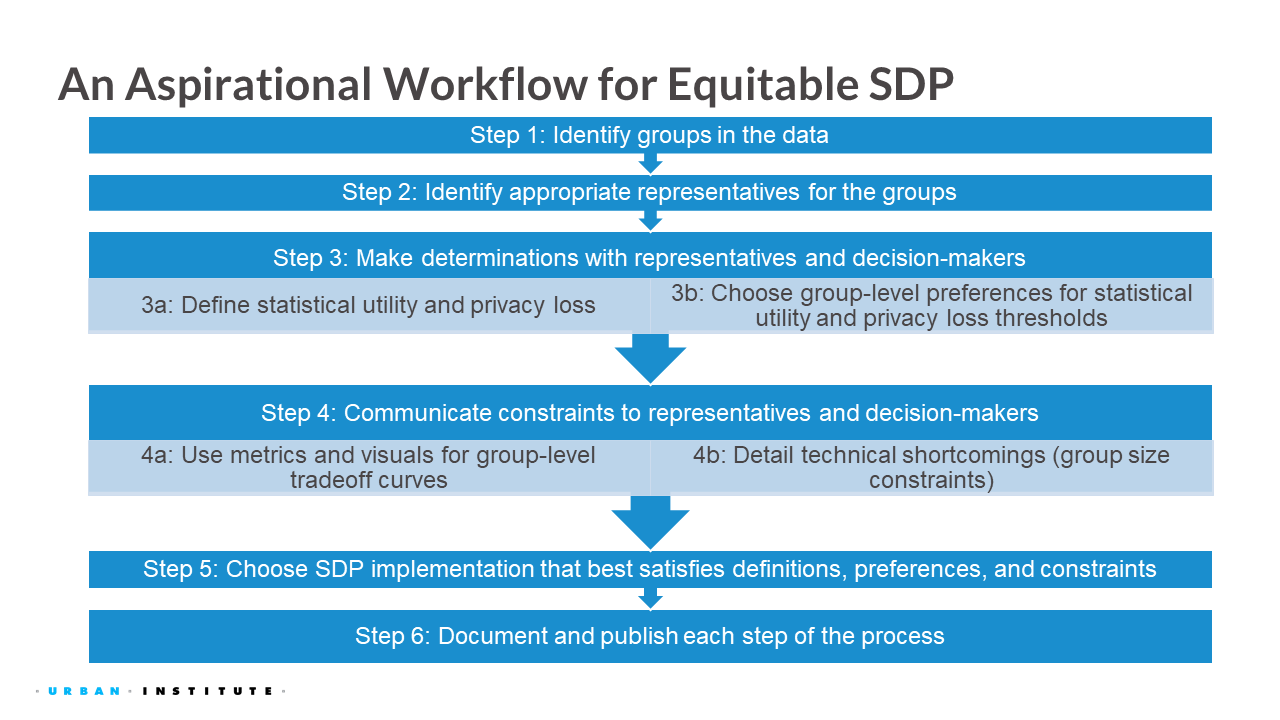

8.3.2 Aspirational equitable statistical data privacy workflow

As discussed in the class activity, there are obvious issues with the previous workflow. This is why Bowen and Snoke (2023) proposed an aspirational workflow. It is called aspirational because we do not expect every step to always be possible in a real-world implementation. That being said, considering these steps can help make equity part of the process from beginning to end. Below, we describe the six steps of the process in greater detail.

Identify groups in the data

Identify appropriate representatives for the groups

Determine privacy and utility definitions and preferences with representatives and decisionmakers

- Define statistical utility and privacy loss

- Choose group-level preferences for statistical utility and privacy loss thresholds

Communicate constraints to representatives and decisionmakers

- Use metrics and visuals for group-level tradeoff curves

- Explain technical shortcomings related to group size

Choose a statistical data privacy implementation that best satisfies definitions, preferences, and constraints

Publish each step of the process

Every step in the process has limitations, so the entire process must be transparent. Because each of the prior steps is aspirational and may require significant growth in the field, transparency is one of the most immediate actions that practitioners can take. The process could be reported in public presentations, documentations, or regular meetings (Murray, Falkenburger, and Saxena 2015; Cohen et al. 2022). This transparency allows outside groups and entities to critique the decisions, offer input during the process, and understand what decisions were made. With feedback, each step of the process can be refined, such as selecting group representatives, choosing preferences, or navigating technical shortcomings.

8.3.3 A Framework for Managing Disclosure Risks in Blended Data

The framework begins with a simple but critical question for agencies considering a data-blending project: What do we want to accomplish with blended data, and why? (Reiter et al. 2024)

Determine auspice and purpose of the blended data project.

- What are the anticipated final products of data blending?

- What are potential downstream uses of blended data?

- What are potential considerations for disclosure risks and harms, and data usefulness?

Determine ingredient data files.

- What data sources are available to accomplish blending, and what are the interests of data holders?

- What steps can be taken to reduce disclosure risks and enhance usefulness when compiling ingredient files?

Obtain access to ingredient data files.

- What are the disclosure risks associated with procuring ingredient data?

- What are the disclosure risk/usefulness trade-offs in the plan for accessing ingredient files?

Blend ingredient data files.

- When blending requires linking records from ingredient files, what linkage strategies can be used?

- Are resultant blended data sufficiently useful to meet the blending objective?

Select approaches that meet the end objective of data blending.

- What are the best-available scientific methods for disclosure limitation to accomplish the blended data objective, and are sufficient resources available to implement those methods?

- How can stakeholders be engaged in the decision-making process?

- What is the mitigation plan for confidentiality breaches?

Develop and execute a maintenance plan.

- How will agencies track data provenance and update files when beneficial?

- What is the decision-making process for continuing access to or sunsetting the blended data product, and how do participating agencies contribute to those decisions?

- How will agencies communicate decisions about disclosure management policies with stakeholders?

8.4 College Scorecard Example

The following description is from Reiter et al. (2024), which I helped write and lead this part of the report. The College Score card is a great example of how to consider the technical and policy solutions to release confidential data for the public good.

The College Scorecard involves an approach to blending aggregated data from the Statistics of Income (SOI) Program of IRS with College Scorecard data (U.S. Department of Education) from the Department of Education (ED).

8.4.1 Determine auspice and purpose

The College Scorecard is intended to help future college students and their families search for and compare colleges by field of study, costs, admissions, economic outcomes, and other statistics. Since 2016, ED has provided the College Scorecard as a web-based search tool (i.e., data product) that users can query repeatedly; public-use microdata files are not required. The unit of analysis is the college, and the data are summaries of the features of the college and its students. ED desired to add earning metrics to the College Scorecard. Such blended data could offer the public additional insights into student outcomes at various educational institutions; however, tax records contain very sensitive information and are protected by Title 26, requiring rigorous privacy guarantees.

From Figure 10.2, we might characterize the College Scorecard containing earnings information as being at the intersection of “Modest Impact” usefulness and “Significant and Lasting” disclosure risks.

8.4.2 Identify ingredient data files

To create the blended data, ED requires earnings data on college graduates. ED therefore turned to SOI for such data. Education data are subject to FERPA, whereas SOI data are subject to Title 26 rules. This means certain fields may be released as is (e.g., institution), but others require confidentiality protection (e.g., earnings data at the field-of-study or institution level). There is no federal source of average earnings per college, requiring the agencies to blend data at the individual student level. Therefore, the ingredient data file from ED includes recipients of federal student aid,3 and the ingredient data file from IRS includes individuals’ earnings. These files need to be linked to accomplish the blending.

8.4.3 Obtain ingredient data files

Because SOI data derive from tax records, individual students’ earnings cannot be shared outside the agency without special agreements. Thus, SOI needs to blend its data with the data supplied by ED. However, Internal Revenue Code (IRC) § 6108(b) permits SOI to release aggregated-level statistics to ED. The IRC authorizes the Secretary of the Treasury to make special statistical studies and compilations involving tax return information as defined in IRC § 6103(b)(2).

8.4.4 Blend ingredient data files

ED provides student-level records—that is, recipients of federal student aid—to SOI to conduct the matching at IRS. The data-sharing arrangement allows SOI to match student information to IRS administrative tax records, which are W-2 (i.e., wage and tax statement) and 1040-SE (i.e., net earnings from self-employment) data. Matching is done on social security numbers.

8.4.5 Select disclosure-protection approaches

For the first 3 years of the product, the College Scorecard used classical disclosure approaches (e.g., data suppression, rounding, aggregation, and top-coding) to protect blended data. During this time, ED and SOI continued to reassess the disclosure risk/ usefulness trade-offs of their dissemination strategy. In 2020, ED and SOI wanted to produce a second data file with greater granularity than available at the institution level—one that contained information at the credential and field-of-study level. But SOI became concerned about potential complementary disclosures in creating two datasets from the same ingredient data, as their disclosure approaches did not account for multiple data releases.

SOI also determined that using the classical disclosure approaches to release the second, more granular data file would suppress and alter substantial amounts of blended data, thereby degrading the potential usefulness of the data product.

In an update of disclosure-protection processes, SOI decided to use SafeTables, a software package developed by Tumult Labs that produces statistics from a formally private, noise-addition algorithm. SOI saw three benefits of using a formally private framework. First was the potential ability to quantify privacy risks when releasing datasets. Second was establishing a privacy-loss budget and a mechanism to examine specific points on the disclosure risk/usefulness trade-off. SOI’s final reason was composition: SOI could potentially track total privacy loss across multiple releases of outputs.4

Although formal privacy methods are used, the approach of ED and SOI to releasing College Scorecard data is a hybrid between formal privacy and classical disclosure approaches. ED and SOI suppress outputs from SafeTables that differ excessively (per their definition) from the confidential data values to enhance usefulness of published data. Therefore, the end product is not technically formally private; the decision to suppress is based on confidential data values, which violates the formal privacy guarantee. SOI accepted the implied higher disclosure risks, suppressing the noisiest results, because the program deemed it important that students have accurate statistics upon which to make potentially life-changing decisions.

Although the privacy community has not fully agreed on a common definition, the U.S. Census Bureau5 defines formal privacy as a subset of SDC methods that give “formal and quantifiable guarantees on inference disclosure risk and known algorithmic mechanisms for releasing data that satisfy these guarantees.”

In general, formally private methods have the following features (Bowen and Garfinkel 2021):

- Ability to quantify and adjust the privacy-utility trade-off, typically through parameters.

- Ability to rigorously and mathematically prove the maximum privacy loss that can result from the release of information.

- Formal privacy definitions also allow one to compose multiple statistics. In other words, a data curator can compute the total privacy loss from multiple individual information releases.

To help determine the privacy-loss budget prior to suppressing values, SOI and ED used an evaluation tool called CSExplorer. Also developed by Tumult Labs, this tool allows the client (i.e., SOI and ED) to review and evaluate the disclosure risk/usefulness trade-offs of the output statistics for various privacy-loss budgets. SOI first used the tool to examine the effects of several privacy-loss budgets on various usefulness metrics. Once SOI identified a set of appropriate privacy-loss budgets, ED had access to a limited version of CSExplorer that was in the range of SOI’s selected privacy-loss budgets. ED then could explore the statistical outputs based on those privacy-loss budgets to examine and decide upon which suppression thresholds to use and other specifications for the final data product release.

This tool allowed ED and SOI to have thoughtful, in-depth discussions about trade-offs between privacy and usefulness.

8.4.6 Develop and execute a maintenance plan

The College Scorecard does not publicize its disclosure-protection processes on its website, and it keeps values of privacy parameters internal. Providing such information along with source code for the disclosure-protection algorithms would improve transparency. Reiter et al. (2024) is also unaware of mitigation strategies for potential breaches.

We conclude this case study by mentioning an application with similar goals as the College Scorecard, namely the Census Bureau’s Post-Secondary Employment Outcomes (PSEO) dataset. This data product provides tables of earnings and employment outcomes of graduates from postsecondary institutions (Foote, Machanavajjhala, and McKinney 2019), although it does not involve IRS data. The PSEO also applies a formal privacy method to publish the tables.

The International Association of Privacy Professionals is a nonprofit, non-advocacy membership association founded in 2000.↩︎

For example, the variables contained in the data, the number of observations, or the range of values for each variable.↩︎

It is important to note that not all students who are in need receive federal student aid, so there may be some bias in generating the College Scorecard.↩︎

Additionally, the use of SafeTables allowed suppression of fewer table cells than would have been required had simple cell suppression been used.↩︎

“Consistency of data products and formally private methods for the 2020 census,” U.S. Census Bureau, p. 43, https://irp.fas.org/agency/dod/jason/census-privacy.pdf↩︎