5 Data Sharing and Transfer

5.1 Importance of sharing data

Fienberg (1994) outlines the ethical, institutional, legal, and professional dimensions for sharing statistical data in biomedical and health sciences, but these ideas apply to all data. I also continue to draw from the guide by ICPSR (n.d.).

5.1.1 Required by law or funding support

One of the foremost reasons for sharing data is that it is often mandated by law or funding sources, such as the National Science Foundation and the National Institutes of Health, two of the largest funders of scientific research in the US. Unfortunately, some researchers are not diligent about following through or find loopholes, such as claiming the information is too sensitive to share or has proprietary aspects.

5.1.2 Scientific rigor

Making data publicly available has several key benefits for the scientific community. It reinforces open scientific inquiry, as the self-correcting features of science work most effectively when data are widely available. It encourages diversity of analysis and opinions, enabling researchers to challenge each other’s analyses and conclusions. It promotes new research and allows for testing new or alternative methods, with numerous examples of data being used in ways the original investigators had not envisioned. Additionally, it improves methods of data collection and measurement through the scrutiny of others. Overall, making data publicly available helps the scientific community reach consensus on various methods.

5.1.3 Cost reduction

Reduces costs by avoiding duplicate data collection efforts. From ICPSR (n.d.):

Some standard datasets, such as the General Social Survey and the National Election Studies, have produced literally thousands of papers that could not have been possible if the authors had to collect their own data. Archiving makes known to the field what data have been collected so that additional resources are not spent to gather essentially the same information.

5.1.4 Training

Data are also an important resource for training the next generation of researchers and for working professionals seeking to improve their technical skills. For instance, think back to your past courses when you were learning a new technical skill. Did it help to have a realistic dataset to test your skills on?

An example the Urban Institute collaborated with the Allegheny County Department of Human Services and the Western Pennsylvania Regional Data Center (WPRDC) to create a synthetic version of the County’s confidential social and human service utilization data. Synthetic data replace actual records in a dataset with pseudo-records, with the goal of closely mimicking key distributional and statistical properties of the original records. This allows agencies to release data disaggregated by race and ethnicity while reducing the risk of privacy violations. Graduate students at the University of Pittsburgh examined the data and confirmed that it could be used effectively, for instance, to allocate resources for overdose prevention.

5.1.5 Data of the people, by the people, and for the people

Finally, I like to say that these data are often “of the people, by the people, and for the people.”

The data are of the people, in the sense that people do care about their privacy and their confidential data. Although they may be willing to trade off information a bit at a time to private sector actors for useful purposes, many people would be deeply unhappy if their personal data was widely available.

The data are also by the people, in the sense that government collection of people’s information is supported by taxpayer dollars. Therefore, one could argue that anonymized individual-level data should be accessible to data users—such as data practitioners, external researchers, or public policymakers.

Literally volumes of research could be cited here about how increased access to government data results in social good for the people.

The reasons for sharing data applies to sharing code.

5.2 Secure data access

Over the years, government agencies have been moving slowly toward allowing more data users direct access to the underlying cleaned data, under strict controls.

5.2.1 Secure enclaves

An example of direct data access is through a secure enclave, such as the Federal Statistical Research Data Centers.1 This secure enclave became available in 1982 (then called the Center for Economic Studies), after data users demanded access to better quality data when the US Census Bureau became more aggressive with its applications of statistical data privacy methods on its data products.

Although more secure facilities are becoming available (for example, the National Science Foundation Secure Data Access Facility2), researchers face several challenges to obtain this direct access. Full access to these data is only available to select government agencies, a limited number of data users working in collaboration with analysts from those agencies, or through highly selective research programs administered by these agencies. Further, data users are often required to be US citizens, undergo lengthy clearance processes to gain direct access (which can take months or years), and submit extensive research proposals.

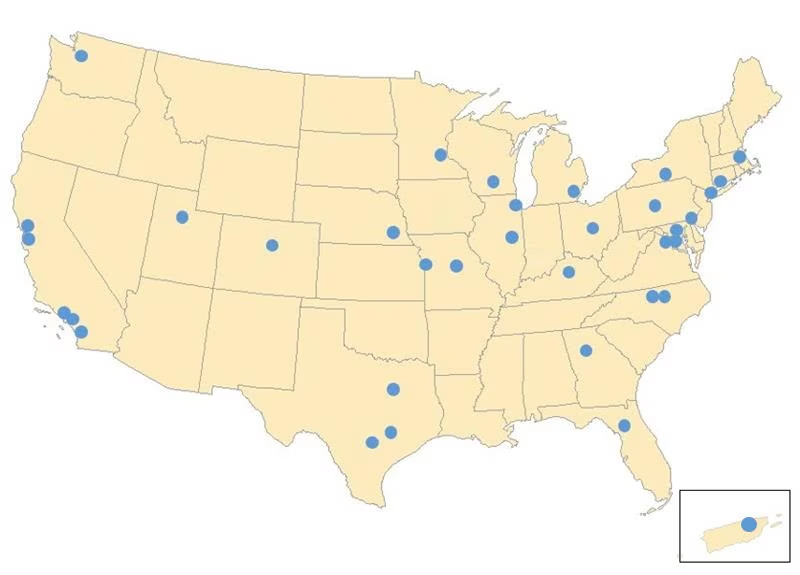

At the time of publication, the textbook mentions there are 30 Federal Statistical Research Data Centers (Bowen 2021). At the time of this course, there are 35. See the U.S. Census Bureau’s webpage on Federal Statistical Research Data Centers for the number and locations.

The 35 Federal Statistical Research Data Centers across the United States (including Puerto Rico!) may seem like enough to be geographically accessible to most data users. But that is not the case. These data centers are primarily located in places with large academic institutions. For me, living in Santa Fe, New Mexico (the state capital), the closest is a 7.5-hour drive to Boulder, Colorado. Moreover, remote access to these data centers grants access to only a limited selection of confidential data and requires a setup that simulates a secure enclave working station, which may prove challenging for many individuals.

5.2.2 Restricted access

Sometimes confidential data will need to be transferred to an external systems for further analysis. The following are two safe options that are standard ensure a secure file transfer:

- File transfer using secure electronic connections. Most workplaces have Secure File Transfer Protocol (SFTP) servers to allow external parties to exchange data with them through encrypted connections. This also includes encrypted emails, file transfers to file hosting services (e.g., Dropbox), survey tools (e.g., Qualtrics), and other services using browser-based transfers with Transfer Layer Security (TLS).

- File transfers using compressed (e.g., zipped), encrypted, password protected files to emails where the password is shared by another means by phone or text message and the encryption is FIPS 140-2 complaint, usually AES 128 or AES 256.

Do not share data through unencrypted file transfers over the Internet or in the body of, or as an unencrypted attachment to, an unencrypted email. Always consider some form of SFTP!

You can also restrict access by limiting the use of confidential variables. For example, if a file is considered confidential because it contains identifying names and addresses, those variables may be removed from the file and replaced with pseudo identifiers. The sanitized file can then be used and shared without risk of violating confidentiality. You can also regulate access restrictions by limiting people within your workplace from accessing specific computer accounts or files.

5.3 Public data files and statistics

The following is discussed in Bowen (2021) and Bowen (2024).

For decades, government agencies produced public use data and statistics. During the pre-computer era in the early to mid-1900s, public use data were available to those who braved the “government documents” section of research libraries or those who physically went to government offices to inspect available files. But government agencies typically reported summary statistics, such as total spending on unemployment insurance and total number of people receiving it. Knowing such information on a county-by-county or metro-area basis did not pose much threat to privacy.

As the computer era arrived, government agencies started to provide more detailed public use data that could be directly accessible to both researchers and the general public. For example, the Statistics of Income Division of the Internal Revenue Service releases a public use file for data users based on administrative taxpayer data. Several organizations, such as the American Enterprise Institute (DeBacker, Evans, and Phillips 2019), the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center (McClelland et al. 2019), and the National Bureau of Economic Research (Bierbrauer, Boyer, and Peichl 2021), develop microsimulation models based on this public use file that inform the public on potential impacts of tax policy proposals.

To ensure that these public use data protect individual privacy, extensive statistical data privacy methods (or statistical disclosure control) are implemented. Here, I will use a fictitious socioeconomic dataset to illustrate a range of such methods. For a more comprehensive overview of these methods, Matthews and Harel (2011) offer a detailed review, while McKenna and Haubach (2019) summarize the specific statistical data privacy methods employed by the US Census Bureau.

5.4 Privacy-Enhancing Technologies (PETs)

Privacy-Enhancing Technologies (PETs) are critical tools for ensuring responsible data stewardship. They help uphold data privacy and security best practices while maintaining compliance with data privacy laws.

Privacy is not only a technical concern but a social contract — between data curators and the individuals whose data is being used. Ethical data use demonstrates accountability to your constituents and broader society.

5.4.1 Common Threats

Threats to Privacy and Data Access

Privacy threats arise from data intruders,who seek to misuse data for harmful or exploitative purposes.

Common threats include:

Reconstruction for proprietary gain: Using released data to reconstruct individual-level information for resale to third-party data brokers.

Reidentification for targeted harm: Reidentifying members of marginalized subpopulations for social, economic, or political exploitation.

Threats to Data Access and Utility

Efforts to protect data privacy can also introduce barriers to data usability.

Overly conservative sharing policies: Excessive suppression of data that limits the usefulness of public datasets.

Cumbersome approval processes: Requiring lengthy or exclusive security clearances for access to restricted-use datasets.

Remember…

- Hackers: adversaries who steal confidential information through unauthorized access.

- Snoopers: adversaries who reconstruct confidential information from data releases.

- Hoarders: stewards who collect data but don’t release the data even if respondents want the information releasesd.

5.4.2 What Are PETs?

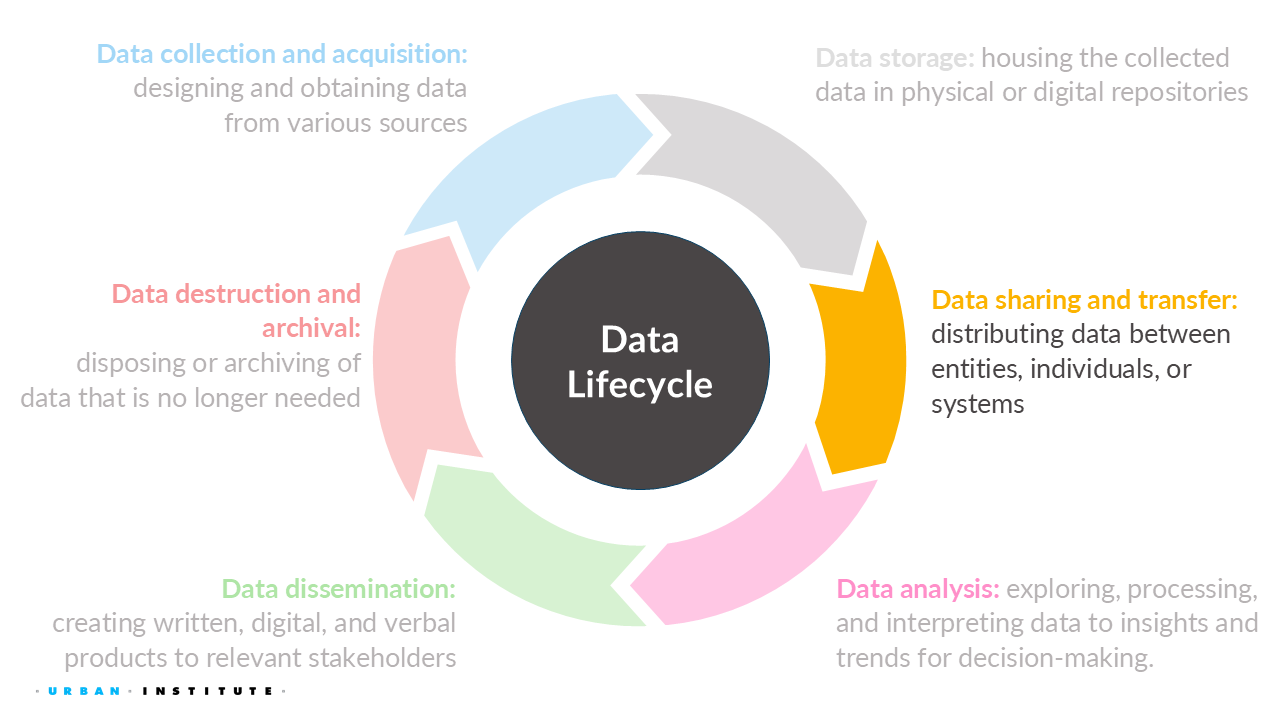

PETs are methods and tools that help reduce privacy risks in different stages of the data lifecycle. They are used in:

- Designing data communication protocols and system architectures.

- Designing data processing algorithms.

- Measuring privacy risks associated with both the above.

Important:

PETs are not plug-and-play. Their effectiveness depends on how they’re implemented and how they’re combined with other techniques.

Two Broad Classes of PETs

Privacy-Enhancing Technologies generally fall into two overlapping categories:

1. Privacy of the Output: reducing disclosure risks associated with specific data and/or data byproducts. Common techniques are…

De-identification - Removing or converting direct identifiers (e.g., names, SSNs).

Statistical Disclosure Control (SDC) - Methods of privacy and confidentiality for output statistics and data. Examples include…

Differential Privacy (DP) - a formal privacy metric framework that analyzes data release processes a priori and paramterizes the privacy protections provided by them.

Synthetic Data - a dataset designed to imitate a confidential dataset while limiting information about individual records in the confidential dataset.

2. Privacy of the Computation: reducing disclosure risks associated with the creation of data and/or data byproducts. Common techniques are…

- Secure Multi-party Computation - subfield of cryptography with the goal of creating methods for parties to jointly compute a function over their inputs while keeping those inputs private.

- Federated Learning - a machine learning technique where multiple clients collaboratively train a model on decentralized, non-identically distributed data without sharing their raw data.

- Trusted Execution Environments - a secure area within a main processor that protects code and data by ensuring confidentiality and integrity, even from the device owner.

- Zero-Knowledge Proofs - a protocol where one party proves to another that a statement is true without revealing any information beyond the truth of the statement itself.

5.5 Statistical Disclosure Control Methods

Statistical Disclosure Control (SDC), sometimes referred to as Statistical Disclosure Limitation (SDL), is a field of study. It aims to develop and apply statistical methods that enable the release of high-quality data products while reducing the risk of disclosure, or release of sensitive information contained in the data.

These methods have existed within statistics and the social sciences since the mid-20th century; researchers have likely encountered some of them before, even outside of the privacy context. SDC can be as simple as:

- suppressing (not releasing or withholding) certain records or results,

- aggregating variables into larger groups (like reporting state-level data rather than county-level data), or

- rounding numeric values to make them less distinct.

Chapter 3 of Bowen (2021) walks through these methods using a famous piece of art. For our class, we will review these methods again, but with a fictitious micro-level socioeconomic dataset.

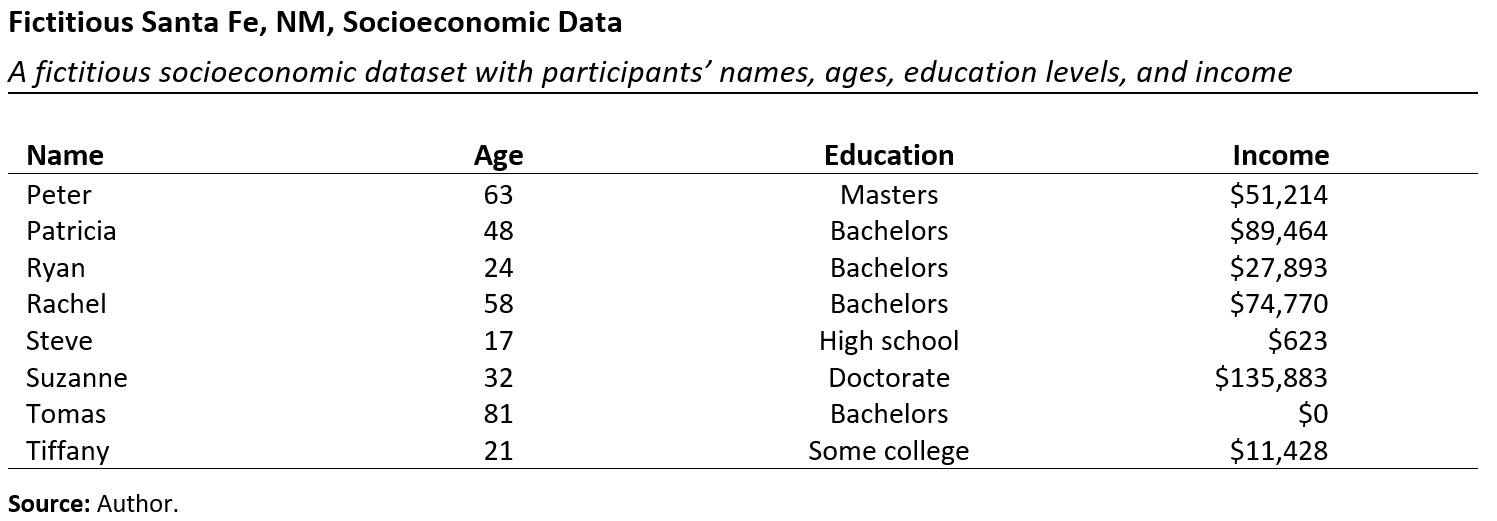

Suppose this fictitious micro-level socioeconomic dataset contains hundreds of records for individuals residing in Santa Fe, NM.

Figure 5.3 displays a sample of eight records from the dataset, which includes the person’s name, age, education, and income.

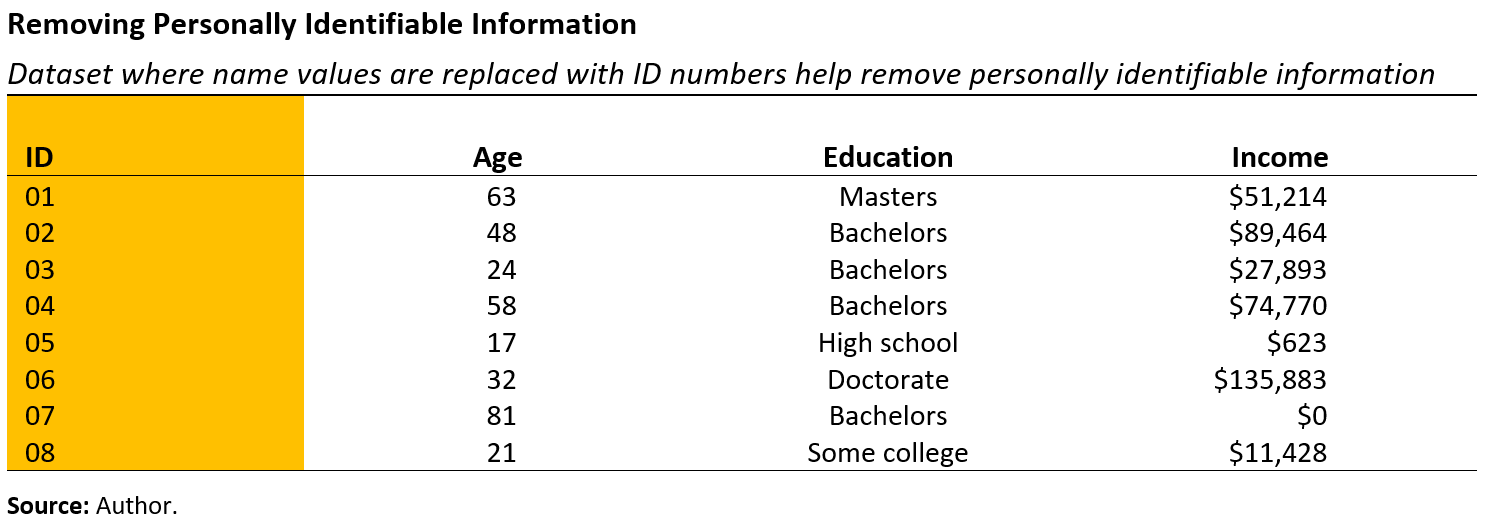

5.5.1 Suppression

As a first step, most personally identifiable information, such as names, should be removed from the data (see Figure 5.4). An obvious step is to replace names with numbers. Data curators, who are responsible for safeguarding the data, may generate individual level identification numbers if they plan to link the data with other information. If there is no intention to link the data with another source, the variable may be entirely removed.

After removing the personally identifiable information, the most common statistical data privacy method is suppression, which involves the removal of certain values from the data. This approach is easy and quick to implement. As an example, when I attended high school in a remote area of Idaho, I was the only Asian American student. Even with names removed, a data intruder could identify me in a dataset that included information on race/ethnicity. To ensure my privacy, such information could be removed or suppressed.

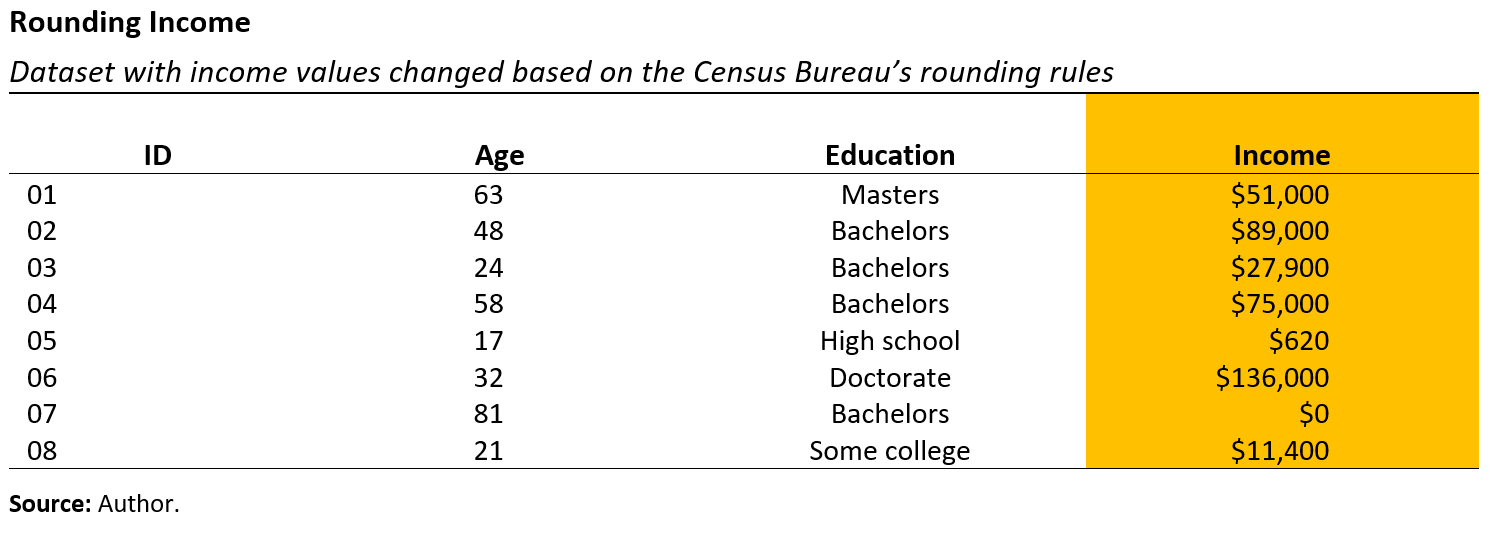

5.5.2 Rounding

Another privacy concern in the fictitious dataset is the reporting of income values to the nearest dollar. To make the records less identifiable, we can round the income values. Instead of rounding to the nearest hundred or thousand, some rounding methods introduce randomization in rounding up or rounding down significant figures.

For instance, consider an individual with an income of $596. If we want to round the value to the closest $10, then there is a 60 percent probability of rounding the income up to $600 and a 40 percent probability of rounding it down to $590.

There are also other rounding schemes, such as the one utilized by the U.S. Census Bureau, which we implement for the fictitious dataset (see Figure 5.5). In this approach,

- $0 is rounded to $0,

- $1–7 rounded to $4,

- $8–$999 rounded to nearest $10,

- $1,000–$49,999 rounded to nearest $100, and

- $50,000+ rounded to nearest $1,000.

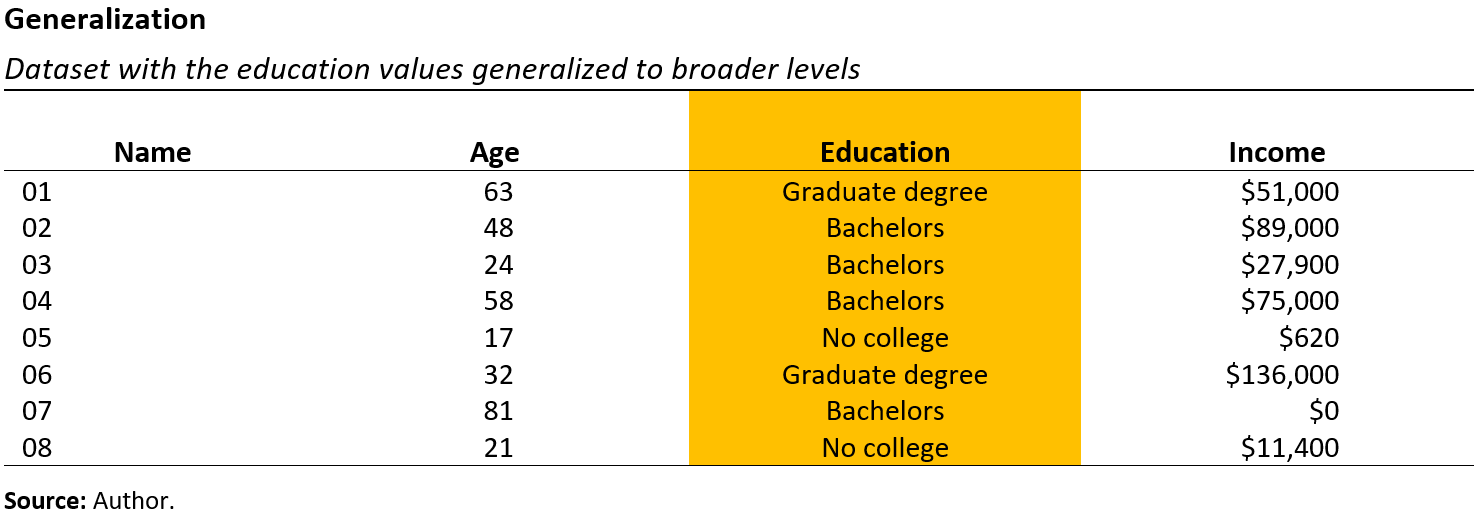

5.5.3 Generalization

Another statistical data privacy method is known as generalization, aggregation, or categorical thresholding. When applying this method, the detailed information is consolidated into broader categories. In our example, we can generalize the education groups, which would decrease or eliminate the number of distinct observations. Figure 5.6 demonstrates how we changed the education levels of “high school,” “some college,” “bachelor’s,” “master’s,” and “doctorate” into broader categories such as “no college,” “bachelor’s,” and “graduate degree.”

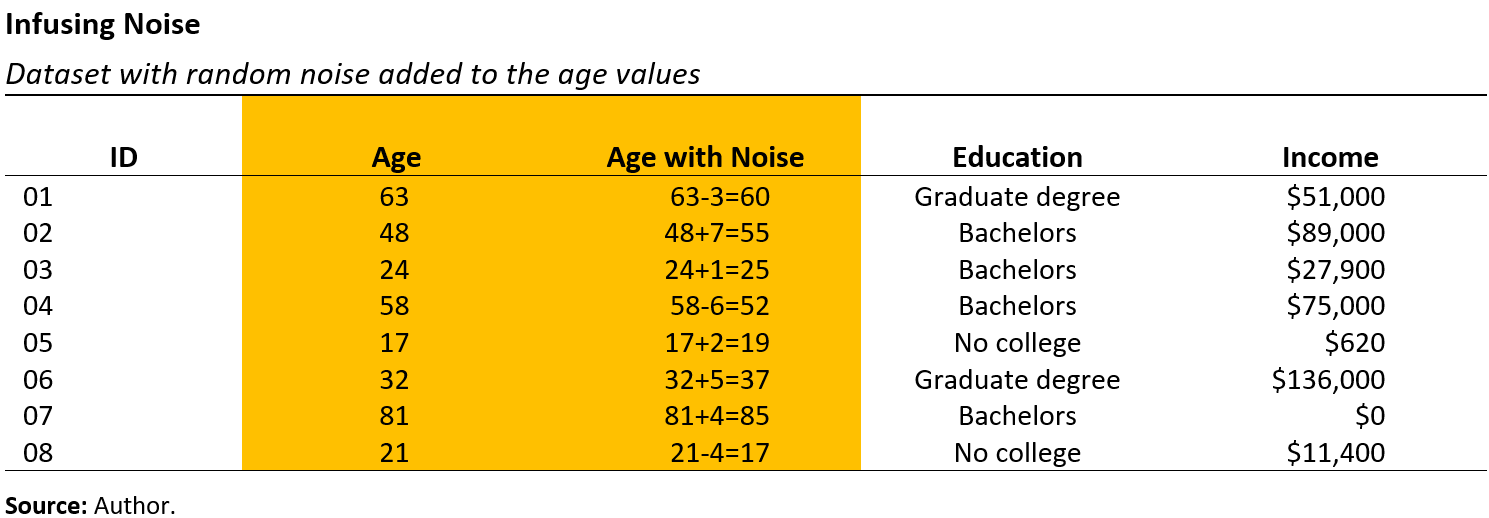

5.5.4 Noise infusion

Adding or subtracting random values is another popular statistical data privacy method. One way to generate random values is within specific boundaries (for example, –10 to 10) or based on a probability distribution (for example, a bell curve centered at zero). This method is known as adding noise, injecting noise, sanitizing results, or perturbing the data. In Figure 5.7, noise has been added to the age variable, resulting in new age values. The random noise is drawn from a bell curve–shaped distribution, such as a normal or Gaussian distribution. We see that some of the added or subtracted values are very small (like 0, 1, and 2), while a few are larger values (for example, 6 and 7). Introducing random values creates some uncertainty, making it more challenging for a malicious actor to discern the original age value.

5.5.5 Top- and Bottom-coding

Top coding/bottom coding limits values above/below a threshold to the threshold value (i.e., individuals over age 95 are recoded to age 95 or a “95 and over” category). For our data, we could top- and bottom-code our Age category to substitute “greater than 85” and “less than 18” rather than the exact values.

5.5.6 Sampling

A common statistical disclosure control approach for protecting microdata files that are released to the public, in addition to such methods as top-coding, is to select a subsample of respondents. The Census Bureau pioneered public-use microdata sample files when it released a 1-in-1000 sample of respondents from the 1960 census.

Statistical agencies use subsampling to introduce some form of “plausible deniability” to protect data in public-use microdata files produced from censuses and sample surveys. The general idea is that if someone tried to identify a record in one released dataset with another publicly available dataset, they cannot guarantee the match is correct because the released data are a random subset of the original.

5.5.7 Synthetic data

In recent decades, synthetic data has become one of the most popular statistical disclosure control methods among privacy researchers. Synthetic data consist of pseudo or “fake” records that are statistically representative of the original, confidential data. Imagine we collect information on where people traveled for a conference in Boston, MA. The confidential data show that 50 out of the 100 participants are already from Boston, MA. One way to generate synthetic data for this sample is to flip a coin 100 times and report the number of heads results as the number of people from Boston, MA.

Statisticians originally developed synthetic data to address missing data in clinical trial scenarios. Patients often drop out of such studies because they last for several months or years. The statisticians created new observations or values for the missing data by developing a model based on the remaining patient data. The idea of synthetic data is attractive to federal agencies because they contain only “fake” records. But most federal agencies don’t use synthetic data yet. This is mostly because of limited human resources (i.e., lack of practitioners who are knowledgeable of the methods and can implement them) and computational resources (i.e., code and proper computing equipment).

In general, synthetic data can be created either based on a model or not based on a model (i.e., with parametric or nonparametric methods). At a high level, the non-model-based approaches calculate the estimates or percentages of counts from the data and use those estimates as weights for a weighted random sampling scheme. Our earlier Boston, MA, conference example would be considered a non-model-based approach, where the weight for the randomization scheme is 50 percent.

Model-based methods rely on estimating or learning an appropriate model based on the confidential data; “fake” records are then created from the model. As an example, suppose we collect the heights of our conference attendees. When we plot the data, we see that the distribution of attendees’ heights is similar to a bell curve or normal distribution and decide to use that model to generate our synthetic data.

The use of synthetic data relies heavily on selecting an appropriate model to preserve the data’s statistical features, and this reliance has a few potential drawbacks. One is that the privacy expert must be careful when selecting and using a model that perfectly replicates the confidential data. Some privacy researchers advise splitting the data into multiple parts so that one part can help inform and develop the model while other parts help verify the model’s quality. Another concern is that if the privacy expert selects a poor model, the synthetic data will provide improper results for data users. This also means that developing a model to capture every interesting feature in more complex data without recreating the confidential data is extremely difficult.

For more technical details on synthetic data, check out Hu and Bowen (2024).

5.6 Taking what we’ve learned so far…

5.7 Week 4 Assignment

Due July 20, at 11:59 PM EDT on Canvas

5.7.1 Read

- Chapter 5: What Makes Datasets Difficult for Data Privacy?

5.7.2 Watch (Optional)

5.7.3 Write (600 to 1200 words)

Find a news analysis story3 published within the last year (2024 – 2025) and answer the following questions:

- What does the article claim?

- Does the content of the article apply to you, your family, and/or your community?

- What makes you believe the conclusions?

- Who wrote the article?

- Where did the article get their facts?

- What “red flags” (if any) do you notice?

- Would the story change if there was more or less access to data? What would be that story?

“Federal Statistical Research Data Centers (FSRDCs) are partnerships between federal statistical agencies and leading research institutions. FSRDCs provide secure environments supporting qualified researchers using restricted-access data while protecting respondent confidentiality.” From the U.S. Census Bureau’s webpage on Federal Statistical Research Data Centers.↩︎

The National Science Foundation Secure Access Facility provides authorized researchers secure remote access to National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics data and metadata, such as the Survey of Earned Doctorates and the national Survey of Recent College Graduates.↩︎

“An article written to inform readers about recent events. The author reports and attempts to deepen understanding of recent events—for example, by providing background information and other kinds of additional context.” – CSUSM Library↩︎